Dead or Alive

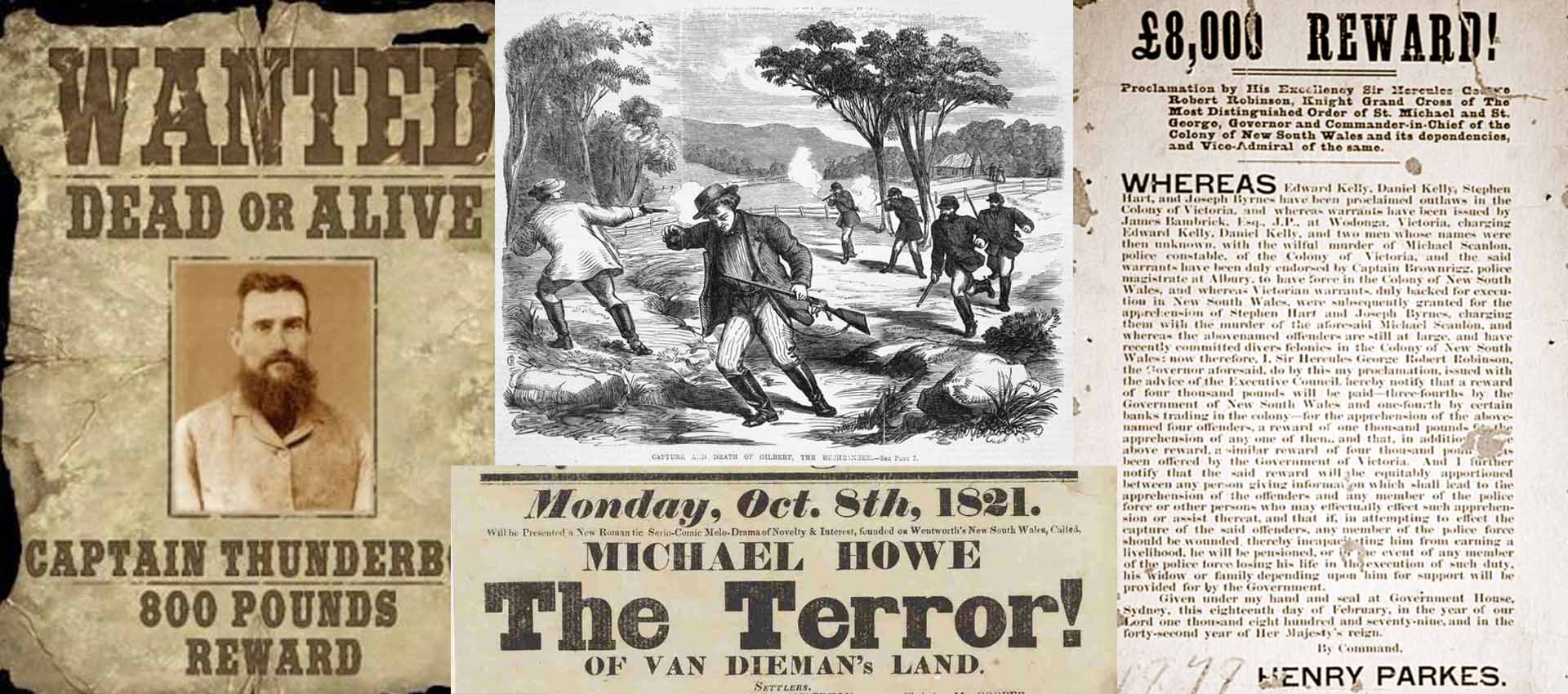

In colonial times the emphasis was on controlling convicts, eliminating bushrangers, and expropriating Aboriginal land by force frequently involving murder. These activities paid little, if any, attention to due legal processes or fundamental legal rights.

In 1830 an ‘Act to suppress Robbery and Housebreaking and the Harbouring of Robbers and Housebreakers’[1] was introduced in New South Wales. The Ordinance provided for a person suspected to be a transported felon at large to be taken before a Justice of the Peace and ‘shall be obliged to prove to the reasonable satisfaction of such Justice that he is not a felon . . . .’[2] This had the effect of reversing the onus of proof, eliminating the inconvenience of the presumption of innocence and effectively the right to silence. The Ordinance also provided for harsh and swift punishment, death two days after conviction, for those convicted of robbery and break and enter offences. It stated:

And whereas it is expedient that robbers and housebreakers should be tried and punished as speedily as may be consistent with the ends of justice. Be it therefore further enacted That all persons who shall be fully committed for the crime of robbery or of entering and plundering any dwelling-house with arms and violence shall be brought to trial as soon as possible and being lawfully convicted of any such crime and sentenced to suffer death shall be executed according to law on the day next but two after sentence passed unless the same shall happen to be Sunday and in that case on the Monday following and such sentence shall be passed immediately after the conviction of such offender unless the Court or Judge shall see reasonable cause to postpone the same.[3]

Reliance on the discretion of a trial judge to determine if death should be delayed effectively removed the right to appeal a conviction, one of the substantive rights that are designed to allow higher courts to determine if an accused has received a fair trial.

The Ordinance had a provision to continue in operation for two years.[4] The law was renewed on a regular basis until 1853.[5] In 1865 ‘An Act to facilitate the taking or apprehending of Persons charged with certain Felonies and the punishment of those by whom they are harboured’, known as the Felons Apprehension Act 1865 (NSW),[6] was introduced into law of the colony. It allowed for a person to be declared an outlaw and apprehended ‘alive or dead’.[7]

The extra judicial death penalty was not a feature of the common law. The diversion from acceptable legal norms by allowing ‘alive or dead’ apprehension is acknowledged by the fact that the Felons Apprehension Act 1865 had a sunset provision of one year.[8] The legislation was to re-emerge with the Felons Apprehension Act 1879 and the Felons Apprehension Act 1899. The use of a sunset clause is designed to ensure that the legislation lapses after a specified period. It is an implicit acknowledgement that the law is not a good one and that it should not be maintained. The removal of the need for a trial by the killing of a suspect removed the need to even consider the application of fundamental legal rights.

The enthusiasm of judges to impose the will of the parliament, even if it involved the death penalty, is seen in a number of decisions. For example, in the Hatfield Bushrangers case his Honour, Sir William Manning, told the prisoners:

It is profoundly sad to see before us four men, such as you are, under conviction for a capital offence, three of you so young. The gaol calendar reports you to be of the ages of 21, 21, and 18, and the fourth stated to be a cripple. But you have unhappily chosen a bad career, and your crimes have brought you to this terrible position. Of the fidelity of the evidence given against you, and the soundness of the verdict pronounced by the jury, I have no sort of doubt; and now the dreadful duty devolves on me of declaring the extreme penalty of the law, that law imperatively imposes the sentence of death. No discretion is left to the Judge. Nor should I, in this case, if a discretionary power had been given to me, think it right to exercise it so as in any way or degree to defeat or hamper that of the Executive to decide on high public grounds, as to the execution of the sentence.[9]

The reports of cases in nineteenth century Australia do not contain full transcriptions of the words said by judges, and the reports are most often found in the newspapers published at the time. However, the harshness of approach seemed to be reflected in a number of cases, and any clemency rested in the hands of the Governor. In 1827 in the piracy case of R v Walton, for example, the Stephen J declared to those he was sentencing that there ‘is a great degree of humanity presiding in the administration of justice in this Colony’ but ‘When at New Zealand, you endeavoured to escape, to get away. Why was it, because force was employed, and you were obliged to give up your piratical design, and surrender to the terms of your captors. In every point of view, your case is of a very aggravated character, for you have abused that clemency, which a merciful and forbearing hand extended to you. The sentence therefore of this Court is, “that you, and each of you, be severally hanged by the neck, until your bodies be dead.”’[10] It is reported that there were 22 prisoners sentenced to death in 1827 but only four were hanged.[11] The tone of the sentencing judges in the 19th Century does not vary greatly from that of many 21st Century judicial officers. The primary difference being that the death penalty has been abolished and sentencing principles further developed.

[1] 11 Geo 1V 10, known as the Bushrangers Act 1830.

[2] Ibid 2.

[3] Ibid 6.

[4] Ibid 10.

[5] See also Offenders Illegally at Large Act 1848 (NSW). In 1854 Western Australia introduced the Suppression of Violent Crimes Ordinance.

[6] 28 Vic 2 11.

[7] Ibid 2.

[8] Ibid 8.

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald, The Hatfield Bushrangers, Thursday 24 April 1879, 6.

[10] R. v. Walton et al. [1827] NSWSupC 7.

[11] Bruce Kercher and Brent Salter (eds), The Kercher Reports: Decisions of the New South Wales Superior Courts 1788 to 1827 (2009 The Francis Forbes Society for Australian Legal History) 844.