Protest Limits and Arrest Powers in NSW

Table of Contents

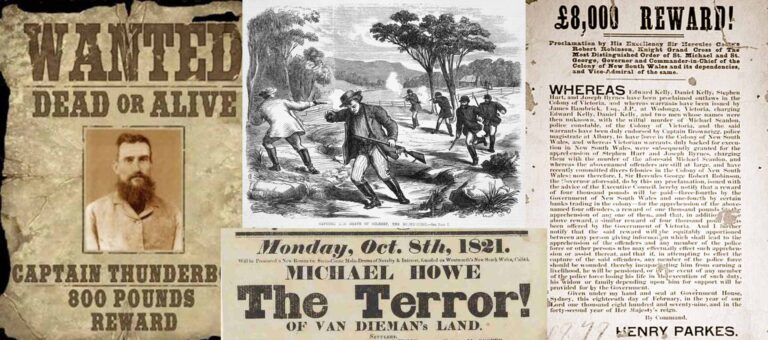

The Tradition of Hate Towards Protesters

One of the most striking examples of the attitude of politicians towards those who protest was shown by the corrupt long serving New South Wales Premier, Sir Robert William Askin GCMG, when he uttered the words, ‘Run over the bastards’, referring to people demonstrating against the Vietnam war who were lying in front of a motorcade containing United States President, Lyndon B Johnson. The attitude of many people at the time was shown by the Prime Minister, Harold Holt’s slogan, ‘All the way with LBJ!’. This love of war approach led to the deaths of many people in Vietnam, and could have resulted in deaths on Sydney streets, when protesters got in the way of the motorcade. Askin’s respect for the law was shown by the encouragement given to illegal casinos which provided cash flows to the underworld and enabled organised crime to consolidate. Askin was a Liberal Premier who won four elections between 1965 and his retirement in 1975. He died on 9 September 1981and left an estate worth $1.958 million. The Department of Taxation determined that ‘a substantial part of Askin’s estate was generated through undisclosed income from sources other than shares or punting and taxed it accordingly’.[1]

Protests Against Environmental Destruction

For many decades people have shown concern about the destruction of the environment and the impact of climate change. These concerns can often be expressed through protests about the activities of companies that pollute and add to the problem of climate change.

People protesting should be aware of the criminal penalties that may be imposed upon them, if they do more than meekly utter a few words of concern. There are a significant number of criminal laws that can be applied to people who engage in protest activities and who come to the notice of the police. Although lip service is given by politicians to the proposition that people have a right to protest, the laws that New South Wales governments have introduced indicate that where vested corporate interests are concerned, any protest that hinders the activities of those interests can result in significant amount of time in gaol and heavy fines.

Examples of Criminal Offences

Some of the examples of the crimes and penalties that can be applied for protesting include the following.

1.. Section 201 of the Crimes Act 1900, which includes a period of imprisonment of 7 years for, amongst other things, hindering ‘the working of equipment belonging to, or associated with, a mine’. There need be no damage to any part of the mine or any equipment related to the mining activity, simply hindering mining activity for an unspecified period of time can result in a crime having been committed.

The definition of hinder, according to the Oxford dictionary, is to ‘make it difficult for (someone) to do something or for (something) to happen’. This very broad definition could make any activity, other than standing quietly away from any road or rail line on public land, subject to a conviction for an offence which carries 7 years imprisonment.

2. Section 213 of the Crimes Act 1900 makes it a criminal offence to ‘intentionally and without lawful excuse [do] an act, or omits to do an act, which causes the passage or operation of a locomotive or other rolling stock on a railway to be obstructed, or assist a person to do or omit to do such an act, with the knowledge that the person’s intention to do or omit to do the act is without lawful excuse’. This type of activity carries a term of imprisonment of two years.

3. Section 214A of the Crimes Act 1900 makes it an offence to damage or disrupt a major facility. As part of such offending a person can be penalised for causing serious disruption or obstruction to a person ‘attempting to use the major facility’ or ‘causes a major facility, or part of the major facility, to be closed’. Additionally, or ‘causes person’s attempting to use the major facility to be redirected’. Imprisonment for 2 years and a fine are available for those who commit this offence. The section does not apply to industrial action: it would apply to people trying to save the environment and who are worried about climate change and cause dispution.

The application of section 214A involves major facilities that can be publicly or privately owned and includes railway stations and infrastructure involving manufacturing, private ports (Botany Bay, Newcastle and Port Kembla), energy facilities, distribution to public facilities and anything described in regulations. Those people who protest by sailing, rowing or swimming in a private port in order to stop the export of coal, are committing a criminal offence if they disrupt coal exports.

4. Section 8A of the Summary Offences Act 1988 makes it an offence to climb or jump from a building or other structure, which includes a bridge or a crane, and can be sentenced to a period of imprisonment of three months. Additionally, such offensive behaviour can include under section 4A fines or 100 hours community service for offensive language ‘in or near or within hearing from, a public place or a school’.

5. If a person decides that they want to protect an old growth forest and, in that process, they obstruct, delay or hinder ‘an authorised officer in the exercise of the officer’s functions’ then under section 83(c) of the Forestry Act 2012 a fine can be imposed, and if the authorised officer is intimidated, threatened or assaulted, then a penalty of six months imprisonment along with a fine can be imposed.

6. Section 545B of the Crimes Act 1900 creates a criminal offence where a person uses violence or intimidation towards another with a view to compelling the other person to abstain from the doing of any act which the other person has a legal right to do. Intimidation is defined as causing a reasonable apprehension of injury to the person. If convicted before the Local Court, the maximum penalty is two years imprisonment or a fine or both can be imposed. In such circumstances protestors need to avoid causing another to feel intimidated because the injury can include to their source of income or an actionable wrong of any nature.

Protesting Not a Right at Law

As can be seen from the above listed offences the right to protest does not extend to environmental activism which involves, amongst other things, blockages, chaining to mining equipment, entering mining sites, disrupting forestry, or hindering the operation of mining or forestry. Such activities apart from the potential to fall under a section of an Act which contains a criminal penalty may also be a breach of the peace. There is no doubt that politicians both Liberal and Labor when in power are in favour of protecting mining and forestry interests. In other words, despite the fact that peaceful assembly is recognised by international law, Article 21 of the International Covenant of the Civil and Political Rights, such a right is heavily constrained such as to not allow people to protect the environment and therefore their physical health and that of others if it causes a hinderance to corporate activities. In effect, New South Wales Parliaments traditionally oppose the right to self-defence against environmental vandalism and the contamination that such activities cause, which can injure and kill. There are many historical examples of the failure of governments to protect communities around industrial sites and more broadly. An example is the Pasminco Cockle Creek Smelter, which was a lead smelter established in 1897 and closed on 12 September 2003. Over 100 years of activity which spread lead throughout the community, gained the support of governments and has left people significantly physically damaged by the waste it spread throughout a very large part of the Newcastle community. Apart from the activities of corporations that can physically harm or kill, the destructive activities they engage in can hinder and disrupt the quiet enjoyment of life of members of the public.

The Australian Constitution although it has an implied freedom of political communication does not confer a personal right to protest: Lange v ABC (1997) 189 CLR520 at 526. The Constitution does not protect those rights which people would generally think they have, for example, the right to liberty.

For those wishing to protest, without suffering a criminal conviction, compliance with section 23 of the Summary Offences Act 1998 is a minimal requirement. This section lists those matters about which the Commissioner of Police needs to be informed. Section 25 of the Act allows the Commissioner of Police to apply to a court for an order prohibiting the holding of a public assembly. Section 26 allows an organiser of the public assembly to apply to a court for an order authorising the holding of the public assembly.

Contained hereunder are some of the principles of law and statutory provisions relating to arrest. Apart from being a participant in a protest, all people should know the following principles and laws. The information provided below is designed as an introduction to the laws. Any person who is arrested should seek the assistance of a legal practitioner, exercise their right to silence and avoid engaging in any activity that gives the arresting police any reason to use force or impose criminal charges.

Arrest the Removal of Right to Liberty

The power to arrest, if arbitrarily applied is a clear breach of the right to liberty. In Donaldson v Broomby, Dean J stated:

Arrest is the deprivation of freedom. The ultimate instrument of arrest is force. The customary companions of arrest are ignominy and fear. A police power of arbitrary arrest is a negation of any true right to personal liberty. A police practice of arbitrary arrest is a hallmark of tyranny. It is plainly of critical importance to the existence and protection of personal liberty under the law that the circumstances in which a police officer may, without judicial warrant, arrest or detain an individual should be strictly confined, plainly stated and readily ascertainable. Donaldson v Broomby (1982) 60(FLR124)

In Cleland v The Queen, Deane J said:

It is of critical importance to the existence and protection of personal liberty under the law that the restraints which the law imposes on police powers of arrest and detention be scrupulously observed. Cleland v The Queen (1982) 151 CLR 1, 26; [1982] HCA 67 at [16].

See also Williams v The Queen [1986] HCA 88; (1986) 161 CLR 278, 9.

Common Law of Arrest

At common law when a person was arrested they were required to be taken before a justice to be dealt with according to law without unreasonable delay and by the most reasonably direct route: Bales v Parmeter (1935) 35 SR(NSW)182 at 189. A failure by police to bring a person to court was described succinctly by Lawton LJ in R v Mackintosh, as unlawful and stupid:

It is important that the police should bear in mind that it is stupid as well as unlawful to keep someone in custody for a minute longer than they should.

R v Mackintosh (1983) 76 Cr App R 177, 182.

In New South Wales, the requirement to bring a person before a court without a reasonable delay has been modified by the parliament to allow for the detention of people arrested for a period of up to 6 hours with a possible extension of another 6 hours.

The law still requires that a person who is arrested be given a reason for his or her arrest, and it remains in most cases unlawful for a person to be arrested for the sole purpose of interrogation. Gaudron J in Michaels v R [1995] HCA 8 provides a helpful description of the common law of arrest.

Arrest a Last Resort

In the second reading speech introducing the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Bill, the then Attorney General, Bob Debus, in effect expanded police powers while making a number of broad statements about the codification of the common law of arrest. Amongst other things, he noted that arrest needed to achieve specific purposes and he attempted to assure those listening that police have the power to discontinue an arrest at any time. He stated, inter alia:

The Government is pleased to introduce the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Bill. The bill represents the outcome of the consolidation process envisaged by the Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service to help strike a proper balance between the need for effective law enforcement and the protection of individual rights ….

I turn now to powers relating to arrest. Part 8 of the bill substantially re-enacts arrest provisions of the Crimes Act 1900 and codifies the common law. The provisions of part 8 reflect that arrest is a measure that is to be exercised only when necessary. An arrest should only be used as a last resort as it is the strongest measure that may be taken to secure an accused person’s attendance at court. Clause 99, for example clarifies that a police officer should not make an arrest unless it achieves the specified purposes, such as preventing the continuance of the offence. Failure to comply with this clause would not, of itself, invalidate the charge. Clauses 107 and 108 make it clear that nothing in the part affects the power of a police officer to exercise the discretion to commence proceedings for an offence other than by arresting the person, for example, by way of caution or summons or another alternative to arrest. Arrest is a measure of last resort. That part clarifies that police have the power to discontinue arrest at any time.

The application of the safeguards contained in part 15 of the bill represents the classification of the common law requirement that persons must be told of the real reason for their arrest and a clarification of the additional requirements that officers must provide their name, place of duty and a warning.[2]

Powers of Arrest Without Warrant

A police officer can arrest a person if that officer suspects the person on reasonable grounds of having committed an offence: section 99(1)(a) of the Act.

Additionally a police officer can arrest a person if the police officer is satisfied that the arrest is reasonably necessary for the following reasons: to stop the person committing or repeating an offence; to stop the person fleeing from a police officer or the location of the offence; to enable enquiries to be conducted to establish the person’s identity if it cannot be readily established or if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that the identity information provided is false; to ensure the person appears before a court; to obtain the property in the possession of the person that is connected to the offence; to preserve evidence of the offence or to prevent fabrication of evidence; to prevent harassment or interference with any person who may give evidence about the offence; to protect the safety and welfare of any person, including the person arrested; because of the nature and seriousness of the offence. The only protection provided is that a person cannot be arrested for an offence for which they have already been tried. Section 99 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 states:

99 Power of police officers to arrest without warrant

(1) A police officer may, without a warrant, arrest a person if—

(a) the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that the person is committing or has committed an offence, and

(b) the police officer is satisfied that the arrest is reasonably necessary for any one or more of the following reasons—

(i) to stop the person committing or repeating the offence or committing another offence,

(ii) to stop the person fleeing from a police officer or from the location of the offence,

(iii) to enable inquiries to be made to establish the person’s identity if it cannot be readily established or if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that identity information provided is false,

(iv) to ensure that the person appears before a court in relation to the offence,

(v) to obtain property in the possession of the person that is connected with the offence,

(vi) to preserve evidence of the offence or prevent the fabrication of evidence,

(vii) to prevent the harassment of, or interference with, any who may give evidence in relation to the offence,

(viii) to protect the safety or welfare of any person (including the person arrested),

(ix) because of the nature and seriousness of the offence.

(2) A police officer may also arrest a person without a warrant if directed to do so by another police officer. The other police officer is not to give such a direction unless the other officer may lawfully arrest the person without a warrant.

(3) The arresting police officer or another police officer must, as soon as is reasonably practicable, take the person who has been arrested under this section before an authorised officer to be dealt with according to law.

Note—

A police officer may discontinue the arrest of a person at any time and without taking the arrested person before an authorised officer—see section 105.

(4) A person who has been lawfully arrested under this section may be detained by any police officer under Part 9 for the purpose of investigating whether the person committed the offence for which the person has been arrested and for any other purpose authorised by that Part.

(5) This section does not authorise a person to be arrested for an offence for which the person has already been tried.

(6) For the purposes of this section, property is connected with an offence if it is connected with the offence within the meaning of Part 5.

(7) In this section—

arresting police officer means the police officer arresting a person under this section.

Any person, other than a police officer, can arrest without a warrant if another is in the act of committing an offence under any act or statutory instrument, or the person has just committed such an offence, or the person has committed a serious indictable offence. Section 100 of the Act states:

100 Power of other persons to arrest without warrant

(1) A person (other than a police officer) may, without a warrant, arrest a person if—

(a) the person is in the act of committing an offence under any Act or statutory instrument, or

(b) the person has just committed any such offence, or

(c) the person has committed a serious indictable offence for which the person has not been tried.

(2) A person who arrests another person under this section must, as soon as is reasonably practicable, take the person, and any property found on the person, before an authorised officer to be dealt with according to law.

A police officer can arrest a person who is unlawfully at large. Section 102 of the Act states:

102 Power to arrest persons who are unlawfully at large

(1) A police officer may, with or without a warrant, arrest a person if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that the person is a person who is unlawfully at large.

(2) A police officer who arrests a person under this section must, as soon as is reasonably practicable, take the person, and any property found on the person, before an authorised officer to be dealt with according to law.

(3) The authorised officer may, by warrant, commit the person to a correctional centre, to be kept in custody under the same authority, and subject to the same conditions and with the benefit of the same privileges and entitlements, as would have applied to the person if the person had not been unlawfully at large.

(4) In this section, a reference to a person unlawfully at large is a reference to a person who is at large (otherwise than because of escaping from lawful custody) at a time when the person is required by law to be in custody in a correctional centre.

Note—

Inmates of correctional centres who are unlawfully at large may also be arrested under section 39 of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999.

Statutory Power of Arrest

The Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 provides the statutory power for police to arrest and detain a person named in a warrant, to enter a dwelling to arrest or detain a person who a police officer believes on reasonable grounds is in the dwelling, once having entered the premises they can be searched. Section 10 of the Act states:

10 Power to enter to arrest or detain someone or execute warrant

(1) A police officer may enter and stay for a reasonable time on premises to arrest a person, or detain a person under an Act, or arrest a person named in a warrant.

(2) However, the police officer may enter a dwelling to arrest or detain a person only if the police officer believes on reasonable grounds that the person to be arrested or detained is in the dwelling.

(3) A police officer who enters premises under this section may search the premises for the person.

(4) This section does not authorise a police officer to enter premises to detain a person under an Act if the police officer has not complied with any requirements imposed on the police officer under that Act for entry to premises for that purpose.

(5) In this section—

arrest of a person named in a warrant includes apprehend, take into custody, detain, and remove to another place for examination or treatment.

Police Powers of Entry

The Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 allows police to enter premises if a police officer believes on reasonable grounds there has been a breach of the peace, or a breach of the peace is about to be committed and they need to enter the premises immediately to prevent the breach. Additionally, they can enter if a person has suffered significant physical injury or there is imminent danger of significant injury to a person and it is necessary to enter the premises to prevent such an injury or further injury. A police officer can also enter if there is a body of a person who has died and there is no occupier on the premises to give consent to entry.

Section 9 of the Act provides the power to enter premises. It states:

9 Power to enter in emergencies

(1) A police officer may enter premises if the police officer believes on reasonable grounds that—

(a) a breach of the peace is being or is likely to be committed and it is necessary to enter the premises immediately to end or prevent the breach of peace, or

(b) a person has suffered significant physical injury or there is imminent danger of significant physical injury to a person and it is necessary to enter the premises immediately to prevent further significant physical injury or significant physical injury to a person, or

(c) the body of a person who has died, otherwise than as a result of an offence, is on the premises and there is no occupier on the premises to consent to the entry.

(1A) Before entering premises under subsection (1)(c), the police officer must obtain approval to do so (orally or in writing) from a police officer of or above the rank of Inspector.

(2) A police officer who enters premises under this section is to remain on the premises only as long as is reasonably necessary in the circumstances.

Breach of Peace

A breach of the peace is classically defined as: ‘whenever harm is actually done or is likely to be done to a person or in his presence to his property or a person is in fear of being so harmed through an assault, an affray, a riot, unlawful assembly, or other disturbance.’: R v Howell [1982] QB 416: [1981] 3 All ER 383.

Police Use of Force

Sections 230 and 231 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 states:

Part 18 Use of force

230 Use of force generally by police officers

It is lawful for a police officer exercising a function under this Act or any other Act or law in relation to an individual or a thing, and anyone helping the police officer, to use such force as is reasonably necessary to exercise the function.

231 Use of force in making an arrest

A police officer or other person who exercises a power to arrest another person may use such force as is reasonably necessary to make the arrest or to prevent the escape of the person after arrest.

What ‘force as is reasonably necessary’ means would vary with each case. The use of force when arresting an accused is not unusual. However, the extent of the force used and whether it was necessary at all may indicate the attitude of the police towards the alleged offender. Further, in cases where a confession has been made, excessive force at the time of arrest may be an indicator of later treatment. Excessive force at arrest may therefore be used in evidence to support an application seeking to exclude a record of interview containing a confession on the basis that the confession was not voluntary. The use of excessive force, if possible to establish, can result in a personal injuries claim and/or the police officer being dismissed from his or her employment or charged with a criminal offence.

Questions That Should Be Answered

The power to question a person without arresting them is very limited, and there is a right to silence, and no police officer can force a person to self-incriminate. Nevertheless, there are some questions that are required to be answered. Section 11 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 requires a person whose identity is unknown to a police officer to give their identity to the police officer, if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that assistance may be able to be given about an alleged indictable offence, because the person was near where the indictable offence was committed, or was there before or after it occurred. Section 11 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 . If the person refuses to disclose their identity they can be fined pursuant to section 12 of the Act. An indictable offence is an offence which can be put in an indictment, which is a document that can be placed before a judge or jury. It is generally considered a more serious offence, although for most people trying to distinguish between an indictable offence and what is called a summary offence, is probably not helpful.

Section 14 of the Act allows a police officer to require the driver of a vehicle to disclose his or her identity, and the identity of any driver or passenger that may have used the vehicle when the police office suspects on reasonable grounds the vehicle was used in connection with an indictable offence. Failure of a driver to disclose his or her identity can lead to a fine or imprisonment, as can the failure of the driver to disclose the identity of any driver or passenger: section 15 of the Act.

Passengers are also required to disclose their identity. Failure of a passenger of a vehicle to disclose identity can lead to a fine or imprisonment being imposed, as can their failure to disclose the identity of a driver or other passenger: section 16 of the Act. Failure of an owner of a vehicle to disclose the identity of a driver or passenger can lead to a fine or imprisonment: section 17 of the Act. Further, section 18 of the Act can lead to a fine or imprisonment if false information is provided.

Police Officers to Provide Details and Give Warnings

As soon as possible, as part of the arrest procedure, a police officer is required to identify themselves as a police officer, unless they are in uniform. They should also give their name and their place of duty. Additionally, they need to give the reason for the exercise of the power of arrest: section 202 of the Act. It states:

202 Police officers to provide information when exercising powers

(1) A police officer who exercises a power to which this Part applies must provide the following to the person subject to the exercise of the power—

(a) evidence that the police officer is a police officer (unless the police officer is in uniform),

(b) the name of the police officer and his or her place of duty,

(c) the reason for the exercise of the power.

(2) A police officer must comply with this section—

(a) as soon as it is reasonably practicable to do so, or

(b) in the case of a direction, requirement or request to a single person—before giving or making the direction, requirement or request.

(3) A direction, requirement or request to a group of persons is not required to be repeated to each person in the group.

(4) If 2 or more police officers are exercising a power to which this Part applies, only one officer present is required to comply with this section.

(5) If a person subject to the exercise of a power to which this Part applies asks a police officer present for information as to the name of the police officer and his or her place of duty, the police officer must give to the person the information requested.

(6) A police officer who is exercising more than one power to which this Part applies on a single occasion and in relation to the same person is required to comply with subsection (1)(a) and (b) only once on that occasion.

Whilst this section purports to require disclosure, section 204A of the Act allows for the validity of anything done even where disclosure is not provided, unless the failure to disclose occurs after the police officer was asked for information.

Arrest for Investigations and Questioning – Part 9

The objects of this part of the Act relate to the detention of people for the purposes of investigation and these objects should to be understood. Section 109 of the Act states:

109 Objects of Part

The objects of this Part are—

(a) to provide for the period of time that a person who is under arrest may be detained by a police officer to enable the investigation of the person’s involvement in the commission of an offence, and

(b) to authorise the detention of a person who is under arrest for such a period despite any requirement imposed by law to bring the person before a Magistrate or other authorised officer or court without delay or within a specified period, and

(c) to provide for the rights of a person so detained, and

(d) to provide for the rights of a suspect who is in the company of a police officer in connection with an investigative procedure but who is not so detained.

Section 109(b) introduces the change to the common law which required a person who was arrested to be brought before the court without a delay. Section 109(d) allows the police to say to a person that they have arrested that they can leave if they want, but they can also stay to be interviewed. Such a person is called a ‘protected suspect’.

Reference to an ‘investigative procedure’ includes questioning by the police of the arrested person. Some safeguards are contained in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 such as the requirement to caution a suspect prior to questioning them, but how official questioning should be recorded is found in section 281 of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986.

Section 110 of the Act makes it clear that a protected suspect must be informed they are entitled to leave.

110 Definitions

(1) In this Part—

detention warrant means a warrant issued under section 118.

investigation period means the period provided for by section 115.

permanent Australian resident means a person resident in Australia whose continued presence in Australia is not subject to any limitation as to time imposed by or in accordance with law.

protected suspect means a person who is in the company of a police officer for the purpose of participating in an investigative procedure in connection with an offence if—

(a) the person has been informed that he or she is entitled to leave at will, and

(b) the police officer believes that there is sufficient evidence that the person has committed the offence.

(2), (3) (Repealed)

(4) For the purposes of this Part, a person ceases to be under arrest for an offence if the person is remanded in respect of the offence.

(5) For the purposes of this Part, a reference to the place where a protected suspect is detained is a reference to the place where the person is participating in the relevant investigative procedure.

Section 110(1) involves a protected suspect who the police consider has committed an offence, but where they want to gather further evidence by conducting a record of interview. The record of interview can be for the purpose of gathering evidence about other people, or gathering evidence from the person being interrogated to reinforce the police officer’s belief that they committed the offence, evidence given by them could ensure their conviction for the offence. It may seem obvious to most criminal law practitioners that if a suspect is told that they can leave after having been arrested they should do so, otherwise they may unintentionally self-incriminate or introduce such ambiguity through their answers that what they say can be regarded as admissions, that is, something said against their own interests. The number of ways that a person who did not commit an offence can create problems by their answers is open ended.

Once a person has been arrested, Part 9, Division 2, of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 applies. Section 114 of Part 9 allows the police to detain a person for the purpose of investigating whether the person committed the offence for which they were arrested. If a police officer forms a reasonable suspicion that the person arrested has committed any other offence, they may investigate that person’s involvement in the other offence during the 6 hour period they are detained.

The power for the police to detain a person only exists once an arrest has been made, section 114 (1) of the Act makes this clear.

If an arrested person is being held for the investigation period, a number of different actions can be taken by the police. They are:

(a) The arrested person can be released unconditionally or on bail within the investigation period (6 hours).

(b) The arrested person can be brought before a court for the purpose of considering whether they are to receive bail or be further held in custody within the investigation period, or as soon as practicable after it ends.

The police cannot lawfully arrest a person for the purpose of questioning him or her. A difficulty can arise when police act unlawfully and arrest a person knowing that they do not have reasonable grounds for that arrest, or that it is reasonably necessary to stop the commission of an offence, or for one of the other purposes identified in section 99 (1) of the Act.

Example of Misuse of Arrest and Interrogation Powers

A good example of a case of misuse of power is found in R v Kemp, Darren [2008] NSWDC 312. In this case Mr Kemp was arrested and placed in a cell with two undercover police operatives and their conversations were recorded. His Honour Nicholson SC DCJ observed that ‘well before the accused’s arrest, Dt Sgt Smith recognised this was a case where he could well do with strengthening up’[3]. His Honour Nicholson stated about the purpose of the arrest:

I am satisfied Dt Sgt Smith’s primary purpose in arresting the accused was to create a situation whereby the accused would be exposed to two undercover police whilst in police custody managed by police, and with all facilities provided by police. Dt Sgt Smith held some hope, if not confidence, that given those circumstances (the accused’s arrest for this particular crime, his noted personality traits as disclosed in other covert surveillance) advantage could be taken of police custody by using facilities of the police station, to obtain a venue, a listening device and his undercover police to focus the accused’s conversation upon the circumstances of the robbery. I am satisfied the two undercover operatives pursued their involvement with the accused at the direction of Dt Sgt Smith for the purpose of achieving, if possible, an outcome consistent with Dt Sgt Smith’s hope for outcome.[4]

His Honour Nicholson described what occurred in the cells as a ‘fishing expedition’, and that nothing in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 or the common law supported the type of conduct the police engaged in. The trickery and subterfuge were designed to overcome the fundamental right to silence and the privilege against self-incrimination. His Honour noted that the arrest of the accused was ‘an unfair deprivation of liberty’, and that it was for ‘an unfair purpose’[5]. Ultimately his Honour rejected the evidence obtained by the police while Mr Kemp was in the cells at Newtown Police Station.

Section 114 of the Act states:

114 Detention after arrest for purposes of investigation

(1) A police officer may in accordance with this section detain a person, who is under arrest, for the investigation period provided for by section 115.

(2) A police officer may so detain a person for the purpose of investigating whether the person committed the offence for which the person is arrested.

(3) If, while a person is so detained, the police officer forms a reasonable suspicion as to the person’s involvement in the commission of any other offence, the police officer may also investigate the person’s involvement in that other offence during the investigation period for the arrest. It is immaterial whether that other offence was committed before or after the commencement of this Part or within or outside the State.

(4) The person must be—

(a) released (whether unconditionally or on bail) within the investigation period, or

(b) brought before an authorised officer or court within that period, or, if it is not practicable to do so within that period, as soon as practicable after the end of that period.

(5) A requirement in another Part of this Act, the Bail Act 2013 or any other relevant law that a person who is under arrest be taken before a Magistrate or other authorised officer or court, without delay, or within a specified period, is affected by this Part only to the extent that the extension of the period within which the person is to be brought before such a Magistrate or officer or court is authorised by this Part.

(6) If a person is arrested more than once within any period of 48 hours, the investigation period for each arrest, other than the first, is reduced by so much of any earlier investigation period or periods as occurred within that 48 hour period.

(7) The investigation period for an arrest (the earlier arrest) is not to reduce the investigation period for a later arrest if the later arrest relates to an offence that the person is suspected of having committed after the person was released, or taken before a Magistrate or other authorised officer or court, in respect of the earlier arrest.

Section 115 of the Act allows a person to be held for a time that is reasonable up to a maximum of 6 hours during the investigation period, or another 6 hours as may be extended by a detention warrant. Section 115 states:

115 Investigation period

(1) The investigation period is a period that begins when the person is arrested and ends at a time that is reasonable having regard to all the circumstances, but does not exceed the maximum investigation period.

(2) The maximum investigation period is 6 hours or such longer period as the maximum investigation period may be extended to by a detention warrant.

Section 116 of the Act provides the criteria that allow for the determination of a reasonable time. Section 118 of the Act allows for a detention warrant to extend the maximum investigation period beyond 6 hours, once for a further period of 6 hours.

Section 120 of the Act provides what information should be included in an application for a detention warrant. Section 121 of the Act allows for the detention after arrest period to count towards any sentence.

Power to Stop Search and Arrest – Part 15 Safeguards

Section 201 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 lists those powers which Part 15, ‘Safeguards relating to powers applies’. Section 201 states:

201 Police powers to which this Part applies

(1) This Part applies to the exercise of the following powers by police officers—

(a) a power to stop, search or arrest a person,

(b) a power to stop or search a vehicle, vessel or aircraft,

(c) a power to enter or search premises,

(d) a power to seize property,

(e) a power to require the disclosure of the identity of a person (including a power to require the removal of a face covering for identification purposes),

(f) a power to give or make a direction, requirement or request that a person is required to comply with by law,

(g) a power to establish a crime scene at premises (not being a public place).

This Part applies (subject to subsection (3)) to the exercise of any such power whether or not the power is conferred by this Act.

Note—

This Part extends to special constables exercising any such police powers—see section 82L of the Police Act 1990. This Part also extends to recognised law enforcement officers (with modifications)—see clause 132B of the Police Regulation 2008.

(2) This Part does not apply to the exercise of any of the following powers of police officers—

(a) a power to enter or search a public place,

(b) a power conferred by a covert search warrant,

(c) a power to detain an intoxicated person under Part 16.

(3) This Part does not apply to the exercise of a power that is conferred by an Act or regulation specified in Schedule 1.

Part 3, Division 3 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Regulation 2016, allows for a support person to be present for a vulnerable person, and for the custody manager to assist with cautioning. A vulnerable person is: a child; a person with impaired intellectual functioning; a person who has impaired physical functioning; an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; and people who are of non-English speaking background.

Caution

Section 122 of the Act requires that a detained person or a protected suspect (a suspect who can leave) needs to be cautioned, that involves telling them they do not have to say anything, but that anything they do say may be used in evidence, they must also be given a summary of the provisions of the Act by a police custody manager. The protected suspect or detained person is requested to sign an acknowledgement that they have received the information.

The requirement to caution has a long history. In R v Swaffield, Kirby J commented on the origin of the caution requirement, found in the Judges Rules and how it can lead to the exclusion of words said by an accused if they have not been cautioned:

The practice of cautioning suspects when interviewed by police has generally been accepted as flowing from the Judges Rules (the rules) formulated in England in 1912 for the guidance of police officers and copied elsewhere throughout the world, including in Australia. … Whilst the rules have never had the force of law in England or in this country, they have continued to provide guidance as to the standards of fairness to be observed when a question later arises as to the admissibility of a confessional statement made to police. In Van Der Meer [1998] HCA 56; (1998) 82 ALR 10, Deane J observed their breach will not automatically mandate exclusion; nor will its adherence to them necessarily prevent it. R v Swaffield [1998] HCA 1 at [139]; (1998) 192 CLR 159

The caution involves advising a person, suspected of having committed an offence, that they have a right to silence, and they do not have to engage in self-incrimination. The number of Australian cases supporting the right to silence is numerous.[6] Gibbs CJ in Sorby v Commonwealth, found that the fundamental common law right against self-incrimination was not protected by the Constitution ‘and like other rights and privileges of equal importance it may be taken away by legislative action’.[7]

In the English case of Lam Chi-Ming v The Queen [1991] 2 AC 212 at 220, the idea that a person could be compelled to engage in self-incrimination was regarded as behaviour that did not belong in a civilised society. It was found that wrongful acts by the police can render a confession involuntary and inadmissible.

The Evidence Act 1995 and case law deal with admissibility of evidence issues where there may be concerns about the context and how a suspected person was cautioned.

Right to Communicate

Section 123 of the Act also allows a detained person or a protected suspect to communicate with a friend, a relative, a guardian, an independent person, or an Australian legal practitioner.

Section 125 of the Act allows the police custody manager to avoid permitting the protected suspect or detained person from contacting a friend, a relative, a guardian, or an independent person if it is believed on reasonable grounds that an accomplice might avoid arrest, or it is likely to result in the concealment, fabrication, destruction or loss of evidence, or the intimidation of a witness, or that it might make it harder to recover property connected to the offence, or could lead to the bodily injury of a person.

References

[1] Murray Goot, ‘Askin, Sir Robert William (Bob)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (Melbourne University Press, Vol 17, 2007) 35-40, cited at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/askin-sir-robert-william-bob-12152.

[2] Hansard, 17 September 2002, p.4846.

[3] Paragraph 46

[4] Paragraph 49

[5] Paragraph 73

[6] Hammond v The Commonwealth [1982] HCA 42; (1982) 152 CLR 188, 3, Brennan J.; Sorby v The Commonwealth [1983] HCA 10; (1983) 152 CLR 281, 5, Gibbs CJ.; RPS v R [2000] HCA 3; (2000) 199 CLR 620, 61- 62 per McHugh J.; Regina v Sellar and McCarthy [2012] NSWSC 934.

[7] [1983] HCA 10; (1983) 152 CLR 281, 298.