What Was It Like For David Harris To Have Schizophrenia?

Table of Contents

David Harris suffered from schizophrenia, but what is schizophrenia and what is it like to suffer from this condition?

Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic mental condition that affects 20 million people worldwide[1] and while it is treatable, it is not curable. It is not a new condition with the earliest description dating to 1550BC in Egypt[2]. People with schizophrenia are up to three times more likely to die prematurely compared with the general population[3] and this is usually due to other medical conditions although suicide rates are significantly higher than the normal population. The symptoms invade every aspect of the sufferer’s life and completely alters the course that their life might have been expected to traverse.

Before The Onset of Symptoms

Prior to the onset of illness, people with schizophrenia are completely normal and experience life the same way as anyone else. There is no prior suggestion that the future sufferer will develop schizophrenia in the future; like the general population, some are highly intelligent, some less so and of course everything else in between.

David’s Experience

David Harris attended a large high school and was a gifted student, often ranked in the top few students and there was no evidence that he displayed behavioural problems.

Prodromal Period

Schizophrenia is often preceded by what is referred to as a prodromal illness and refers to the appearance of ‘early, morbid, nonpsychotic behavioural changes that occur before the onset of a schizophrenic psychosis’[4]. The future sufferer begins to experience uncomfortable feelings; they cannot make sense of what is happening to them. Typically, it is difficult or impossible to identify the symptoms and the nature of these symptoms remains unclear to researchers[5]. These internal changes are usually expressed in a change in behaviour too. Sometimes, these changes are subtle, and the individual becomes quieter and withdraws from people around them and, at the other extreme, behaviour can become aberrant and even antisocial.

David’s Experience

When David was around the age of fifteen, his family noticed that he changed. In spite of his previous academic excellence, he suddenly lost interest in schoolwork and left school. He managed to get an entry level job with the public service, but it was not long before he was socialising with some other young employees and together, they drank regularly and began using marijuana.

The First Psychotic Breakdown

At some point, a patient developing schizophrenia is affected by the first psychotic symptoms of acute schizophrenia. The symptoms can seem to appear rapidly, although often, they have been slowly developing without being noticed by the people around the patient. However, even if the symptoms are not immediately obvious, or the sufferer has been able to conceal symptoms for some time, at some point it does become obvious. This sometimes occurs at around the same time the person loses ‘insight’. This means that the person is no longer able to recognise that their experiences are not real, and they fall into a delusional system which increasingly controls their thoughts, emotions and behaviours.

The Central Symptoms of Acute Schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia experience a range of symptoms during the acute phase of the illness. There are many symptoms but the following few are the core symptoms that are almost always detected:

Abnormal Thought Content – Delusional Thinking

Delusional thoughts can be described as:

“a belief that is clearly false and indicates an abnormality in the affected person’s content of thought. The false belief is not accounted for by the person’s cultural or religious background or his or her level of intelligence. The key feature of a delusion is the degree to which the person is convinced that the belief is true. A person with a delusion will hold firmly to the belief regardless of evidence to the contrary.”[6]

This means the affected person experiences unshakable abnormal ideas that are not shared by others in their culture. They cannot be talked out of the belief, even if strong logical arguments are put forward. The content of delusions varies from different individuals, but they are usually ‘bizarre’ to others although there are common themes including:

- Religious ideas such as believing that someone is possessed;

- Paranoid ideas like being watched by someone or something such a government or some other authority;

- Ideas of being controlled by someone or something. For example, an affected person might describe that someone is controlling their movements and behaviours;

- A belief that thoughts are being inserted into their head beyond their control. Sometimes this experience might be attributed to a particular person, but usually this is not the case, and the affected person just feels perplexed.

Abnormal Thought Processes

When a person is experiencing acute psychotic symptoms they often experience abnormal patterns of thought, usually referred to as ‘thought disorder’[7]. There are various ways of describing these patterns and these patterns are beyond the scope of this article. To many people, it might simply sound like the things being said sound odd or unusual, and in some cases, words, phrases and sentences can be completely non sensical. A psychiatrist trained to detect these patterns will be able to identify and categorise them

Hallucinations.

Simply put, an hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus[8], however, it is more complex than this. An hallucination can be simple and comprise nothing more than a noise that has no basis, or it can be complex and include something like a voice talking to the affected person when there is no one there. Like delusions, there can be many different hallucinatory experiences although most people who experience hallucinations, especially during the first episode of psychosis, will feel at least anxious about these unexplained experiences and more often, feel fearful of the experience.

Treatment of the First Psychotic Breakdown

Most people experiencing their first psychotic breakdown will be managed in a psychiatric hospital. This is partially because the symptoms have already become severe as neither the patient nor their family and friends understood what was happening. However, the loss of insight, or not being able to understand that the delusions and hallucinations are part of an illness, prevents the patient from seeking treatment. Instead, a patient in this situation is often ‘scheduled’ and hospitalised and treated against their will under the local mental health act[9].

Treatment at this stage typically involves specific antipsychotic medications which alter chemical pathways in the brain to correct the pathways that are currently not functioning properly. Often, other sedating medications are also used to help settle agitation and resolve sleeplessness. The combination of modern medications is effective in more than 80% of cases[10] and, while it is usually recommended that patients continue medication for at least one year, as many as 90% of patients discontinue medication well before this[11]. The most important reason for this is the side effect profile of antipsychotic medications. Most patients complain of disabling side effects caused by the medication. Depending on the medication prescribed these side effects include tremors, dribbling, inability to sit or stand still, tongue rolling around in the mouth and slowed thinking. The side effects are undoubtedly difficult to tolerate.

David’s Experience

David’s first psychotic episode presented in his teenage years, and he was treated in Cumberland Hospital, a psychiatric inpatient hospital in the western suburbs of Sydney. At the time he had paranoid and religious delusions with hallucinations. He was treated with one of the antipsychotic drugs available at the time which universally caused unpleasant side effects and there is no doubt David would have experienced these side effects.

Following An Initial Psychotic Episode – Chronic Schizophrenia

While 80% of patients who present with a psychotic episode are successfully treated with antipsychotic medication[12], this also means that 20% do not and continue to experience ongoing psychotic symptoms. However, for the majority whose psychosis does abate, there are several possible outcomes. First, this might have been a one-off event and they will never experience a psychotic event again. In these cases, the psychosis might have been triggered by drug use or some other circumstance but whatever the cause, it would not meet the criteria for schizophrenia. Second, they might have had a psychotic episode as part of another psychiatric condition such as a psychotic depression or mania, and they will follow a course known for that particular disorder. Or third, they have schizophrenia and will go onto experience the problems associated with this disorder.

Having schizophrenia usually implies a patient will experience further acute psychotic episodes, often described as ‘positive’ symptoms, while simultaneously developing chronic ‘negative’ symptoms.

Acute Psychotic Episodes and Positive Symptoms

Following an initial psychotic episode, patients usually experience further acute episodes in the future, particularly in the earlier stages of illness. The presentation is often similar to the initial episode, including consistency of delusional content and the nature of the hallucinations. In some situations, these ‘positive’ symptoms become set in and don’t fully abate but the patient has enough insight to ‘know’ the experiences are a product of illness. However, the attainment of insight can be tenuous, and the patient feels a constant state of perplexed apprehension and fear.

Negative Symptoms

Between acute episodes, someone with chronic schizophrenia is increasingly affected by the impact of the so-called negative symptoms of schizophrenia. While it is more complicated, these symptoms are often characterised by motivational loss, slowed thinking and affective blunting. Blunting is best described as experiencing life as though from behind a pane of glass; you can see the other person, but you can’t reach them.

The effect of this is that people with chronic schizophrenia find it increasingly difficult to engage with life as most people do. They withdraw from people and become more consumed by their inner world while their occupational and social ability is diminishing.

Functional Deterioration

In the late 1899 Emil Kraepelin described the signs of a condition he called dementia praecox[13] which literally meant premature dementia or premature madness. This went on to be called schizophrenia however, the name Kraepelin gave to this condition is useful in that it described the natural course of the illness. That is, people with chronic schizophrenia experience an inexorable decline in function over time, often in a step wise fashion, with each deterioration heralded by an episode of acute symptoms. Another way of thinking about this would be that when a person experiences an acute psychotic episode, even though they might improve, residual damage remains.

David’s Experience

David followed the typical pattern of schizophrenia described above. He presented with an initial acute episode of illness in his teenage years and, in the decades following he became increasingly withdrawn and ‘odd’ to other people while also being admitted to Cumberland Hospital on 29 occasions for episodes of acute psychosis.

His acute care was typically managed in hospital while his chronic care was managed in a community care setting. He lived in public housing with support, which suggested he was better than some who required management in a group home setting from a young age. Nonetheless, he required support and his social interactions were abnormal. For example, his reluctance to use telephone communication and rely on using mail was potentially a product of maintaining distance, perhaps as a consequence of chronic paranoid ideas that calls were being listened to. When his parents passed, David showed no emotion as a reflection of his affective blunting.

The Cause of Schizophrenia

The strongest risk for developing schizophrenia is having a first degree relative with schizophrenia. This implies that schizophrenia is a genetic disorder although gene studies have not identified a straightforward gene linkage to the illness. Instead, geneticists believe it is caused by a combination of multiple common variants[14]. In 1987, Weinberger postulated that schizophrenia could be a neurodevelopmental disorder of brain connectivity, or how our brains are wired, and that it is simply a variant of brain structure[15] development of something that is immensely complicated and contributed to by the interaction of thousands of ‘risk genes’ and environmental factors.

The reality is that even now, a definite cause of schizophrenia is not able to be clearly defined and for most people, understanding that it is caused by a combination of genetic risk factors, perhaps mixed with environmental factors will have to be enough, vague as it is.

The Role of Substance Abuse in Schizophrenia

Substance abuse can cause an acute psychotic episode resembling schizophrenia, but substance abuse does not cause schizophrenia. People who experience a drug induced psychosis typically experience a complete resolution of symptoms and do not go on to have further spontaneous psychotic episodes or experience the other chronic symptoms of schizophrenia.

However, some street drugs like cannabis, cocaine, LSD and amphetamine can trigger psychosis in susceptible individuals. This means individuals with genetic risks can be triggered by using psychoactive drugs and, even if they didn’t use drugs at that time, they would develop illness at some later time anyway. Nonetheless, drug use is common in people suffering from schizophrenia. Different studies vary in their report of the prevalence of drug misuse in schizophrenia, but one recent study demonstrated that 11.9% of schizophrenic patients had a comorbid substance abuse disorder[16] and another study demonstrated that as many as 80% have used illicit substances or abused alcohol at some time in their life[17].

Given that psychoactive drugs can, by their very nature, exacerbate psychotic symptoms in a sufferer, or even cause psychotic symptoms themselves, many people wonder why someone with schizophrenia might abuse these drugs. During the prodrome phase of the illness future patients are already experiencing perplexing symptoms they can’t explain. This may include things like the beginnings of hallucinations, odd thoughts they can’t explain or a ‘delusional mood’ which makes them feel perplexed, fearful and anxious. They might have told someone, even a GP, but at this stage the symptoms are vague and difficult to interpret so they go on undiagnosed and untreated. These people may venture into drug use, often cannabis, and find that in the short term it helps to quieten their mind and perhaps reduce some of the symptoms they are already experiencing. The same motivation can occur during future episodes of acute illness and during the chronic phase where they might be experiencing a dysphoric sense of unease and again, illicit drugs can provide a short-term solution. There can be other motivations, such as believing that street drugs are as good as prescribed medication and with fewer side effects, or using the drugs to help them focus on their paranoid symptoms as way to ‘outwit’ the perceived persecutors, and a sense of hopelessness that can be temporarily relieved by drug use[18].

David’s Experience

During the prodrome phase of David’s illness he left school prematurely and even though he was working, he began using drugs and alcohol with a couple of other young men he met in the workplace. Superficially this might have been seen as a need to belong by joining a small social group where substance abuse was normalised, or perhaps the defiance of a young man in his late teenage years attempting to defy his parents expectations. However, given that he was already displaying changes in his behaviour, it is more likely that he was already experiencing prodromal symptoms and the opportunity to try cannabis at this stage of his life came from a desire to quieten some of the symptoms he was already experiencing.

Similarly, during his adult life he used cannabis from time to time, and while the medical professionals and his family would have tried to dissuade him, his actions may have been motivated by a desire for some temporary peace from his experience and feelings of hopelessness caused by the illness he suffered from.

Life Expectancy

Schizophrenia shortens normal life expectancy. A meta-analysis that included nearly 250,000 patients across Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia and North America demonstrated that the average age of death of men with schizophrenia was 59 years, and women with schizophrenia was 63 years.[19] There were continental differences although North America, Europe, Australia and Asia were similar. The African results were much worse with the years of potential life lost as much as 28 years[20].

Deaths can be categorised as death from natural causes, death from accidents and death from suicide.

Death By Suicide & Accident

Suicide is an important cause of death for people with schizophrenia, particularly in the earlier stages of the illness with 71% of suicide deaths occurring within the first three years of the illness[21]. Research into the suicide rates in Denmark in the first five years of a diagnosis of schizophrenia demonstrated a suicide rate of 5.5%[22]. However, this figure is probably higher if you take into account the recording of accidental deaths which often include suicides that have been incorrectly classified[23] because they were either undetected or for social reasons. These suicide rates are much higher than those of the general population which currently stands at 0.012%[24].

Parasuicide refers to suicidal behaviour or attempting suicide and is much more common with parasuicidal behaviour being observed in as many as 27% of schizophrenic patients in the earlier stages of their illness[25]. Again, this means that parasuicide is much more common in people with schizophrenia that the general population where lifetime prevalence of parasuicide is between 0.72 – 5.9%[26] and most cases occur in young women[27].

Death By Natural Causes

People with schizophrenia are more likely to die from diseases experienced by the general population, but at a significantly higher rate and at an earlier stage of life. Cardiovascular disease mortality is four-fold higher in patients in the age between 18-49 and twice as high in patients 50 years and over[28]. Cancer related deaths follow a similar pattern to cardiovascular disease[29] while in Asia, 66% of deaths are caused by infection[30].

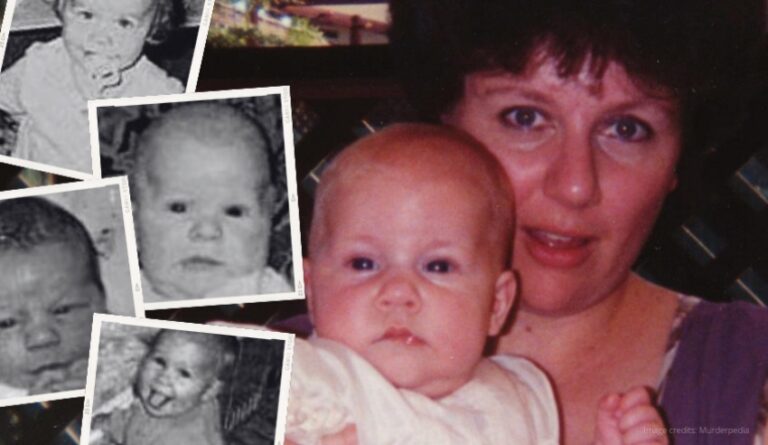

David’s Experience

David experience suicidal thoughts and feelings in the earlier stages of his illness and attempted suicide on several occasions. At one point he had a girlfriend who also had psychiatric illness and she successfully killed herself.

David was not known to have cardiovascular disease or cancer and he died at the age of 56 years, which is three years short of the average age of mortality for people with schizophrenia. To date, and in spite of an autopsy, his cause of death has not been able to be determined because of the advanced decompensation of his body when he was eventually found at least a couple of months after his death.

A Brief History of Managing of People with Schizophrenia

A Transition from Community Care to Lunatic Asylums

In the UK, Bethlem Royal Hospital was the first hospital established and opened in 1247 and it began to admit patients with mental conditions around 1407. However, most people with mental conditions were cared for by the family until the rise of the Victorian era lunatic asylums in the late 1700’s. Parliament began setting the stage for standards of care in asylums although there were severe short comings. The control was initially centralised under the Madhouses Act 1774[31] but in an effort to encourage local care, this was replaced by the County Asylums Act 1808[32]. This was replaced by the County Asylums Act 1828[33] to try and deal with problems related to mentally ill patients being transferred to prisons and then, in 1845, the Lunacy Act[34] which created a commission to oversee the performance of asylums; require asylums to be registered with the commission; ensure asylums had regulations; and ensure each asylum had a resident physician.

Abusive ‘Therapies’ to Crude Medical Management

Even object of the asylums appears to have been to benefit afflicted people, the available treatment was not beneficial, and would be better described as harsh, cruel and inhumane. People were exposed to a wide variety of ‘treatments’ including beatings, being tied up, mechanical restraints and straightjackets. In the US in the early 1900’s and on the basis of a misguided theory that mental illness was caused by an infection of the body, patients had parts of their body removed including pulling teeth and removing tonsils, stomachs, small intestines, appendixes, gallbladders, and thyroid glands[35].

As medicine progressed, frontal lobotomies were devised in 1949 by a neurologist, António Egas Moniz, for which he won a Nobel Price for Physiology in Medicine[36]. This treatment involved inserting a large needle resembling an ice pick into the brain which was accessed in the eye socket above the eyeball and then macerating the brain tissue by moving the needles back and forth damaging the brain in the pre-frontal cortex. The so-called benefit was that the formerly agitated patient became docile and compliant. They may not have had continuing symptoms, it is hard to know, but they had little or no activity which was regarded as a successful treatment.

Antipsychotic Drugs

The first medication to be used as an antipsychotic agent was chlorpromazine, which was a phenothiazine derivative that had been used for it antihistamine effect. In 1951, it was administered to patients during surgery for its antihistamine effects. Soon after, it was administered it to psychiatric patients for the same reason and coincidentally the doctor noticed its antipsychotic effects[37]. In other words, the discovery that it had antipsychotic properties was a complete accident. Chlorpromazine is still available and used to this day. What’s more, newer drugs are probably no more effective on positive symptoms, but they do have different side effect profiles that make them easier for patients to tolerate[38] and newer drugs may have some impact on the development of negative symptoms.

De-Institutionalisation

Like the UK, Australia relied on institutional care to house and treat psychiatric patients, particularly people with schizophrenia who tended to stay in hospital permanently. This meant that they usually started in an acute care ward and then moved to the ‘chronic wards’ which were smaller cottages housing a handful of people with illness.

In 1983 the NSW government published the Richmond Report[39] which followed an Inquiry into Health Services for the Psychiatrically Ill and Developmentally Disabled by David Richmond. The author notes that the exodus of patients from institutions had already started, but this was not an attempt to provide better care for people suffering from illness, it was because of a process of defunding. The report made recommendations that people should be managed in a community setting where possible, but stipulated that this required funding to follow the service providers, and the service providers needed cultural development to ensure good care.

Some community treatment centres did develop and for a time they did have funding to provide a 24-hour service to community-based patients with a variety of psychiatric illnesses including schizophrenia. They also maintained a smaller acute care ward to deal with acute admissions before seeing them back in the community with comprehensive care. In locations where this was occurring, it was a successful program and there is no doubt that patients benefited from an improved lifestyle and better general care. However, funding again started to shift away and there have been increasing problems associated with service reductions caused by funding reductions.

The Introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS)

A report prepared by the Productivity Commission into the development of a long-term disability care and support scheme in 2011 and this led to the development of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013[40]. The act has a number of objectives[41] which include, among others, the provision of:

- Support for the independence and social and economic participation of people with disability;

- Reasonable and necessary supports;

- Choice and control in the pursuit of goals.

While the NDIS creates a Commission to manage its services, it does not directly provide services to NDIS clients. Instead, an industry of private service providers[42] has grown to provide direct services to clients who have been approved by the Commission. However, as much as the act seeks to create a high ideal of care for disabled people in our community, there have been many reports of difficulties in its implementation[43].

Mental health problems were the last group to be added to the NDIS, but even now, it can be a challenge for people with mental health problems to access services. Problems relate to a workforce that is not trained to service people with mental illness, inflexible care plans that do not consider mental health issues, and difficulties coordinating services[44].

David’s Experience

David’s diagnosis was made in the early 1980’s, at about the time the Richmond Report was being considered and published. He would almost certainly have been treated with chlorpromazine and/or one of its close relatives at that time, all of which caused significant, unpleasant side effects.

His care over the next 30 years has been influenced by the outcome of the Richmond Report – he has spent the bulk of his time in the community with the support of the local mental health team and acute episodes were managed in hospital. However, he has also been affected by the impact of gradual defunding of these services, the penultimate outcome being that he was discharged from care in 2018. His medical file indicates that he was now stable and could be discharged but this decision must have been influenced by a lack of resources. While he had been experiencing fewer acute psychotic symptoms, he was obviously affected by the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and nearing an age where people with schizophrenia are known to perish. Making matters worse, while there was an attempt to arrange follow up with a GP, this was not followed through by the mental health team to ensure David was connected to his new doctor. The notion that someone who had such a long illness with many acute episodes would be discharged from care is only possible to understand from an administrative perspective, there is no possible way this was clinically indicated.

In a parallel time-frame, he gained access to NDIS support in 2017 and while he did receive support services, it appears that the criticisms made about the NDIS in relation to mentally ill patients apply to David’s experience. The malalignment of his needs was so stark that the NDIS withdrew their services weeks before abandoning him to die.

Closing Remarks

Schizophrenia is a severe, disabling psychiatric disease that has been described in literature going back as far as Egyptian times. While people were managed in the community with the family prior to industrialisation, widespread institutional care commenced in the late 1700’s and continued in Australia until the 1980’s and 1990’s when a concerted effort to move back to community care began sweeping through the institutions.

Sadly, while it started with a hopeful purpose, like so many times before it, funding, or more specifically, defunding has played a negative role and the care of mentally ill patients. Care remains poor and is getting worse as the process of defunding continues. The poorer general health of people with schizophrenia is so marked that they are expected to survive more than 17 years less than the population average. Worse still, their lifestyle during their time with illness can only be described as impoverished and lonely.

The advent of the NDIS brought hope to many and it was able to provide support to mentally ill patients, but it failed to identify the way it should provide support. Most importantly, the NDIS is not a replacement for ongoing medical or psychiatric care.

The case of David Harris shows a man who has followed an almost prototypical example of a man with schizophrenia, including his age of diagnosis, concurrent substance abuse, chronic symptoms, being pushed from service to service, self-enforced isolation, and his untimely early death.

Surely a modern society should be able to do better.

References

[1] GBD, ‘Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990-2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study’ (2018) The Lancet.

[2] N Burton, Living with Schizophrenia (Acheron Press, 2012), p3.

[3] Laursen TM, Nordentoft N and Mortensen PB, ‘Excess Early Mortality in Schizophrenia.’ (Pt 10) (2014) Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 425-438.

[4] Juan Bustillo, Robert Buchanan and William Carpenter Jr., ‘Prodromal Symptoms Vs. Early Warning Signs and Clinical Action in Schizophrenia’ (1995) 21(4) Schizophrenia Bulletin 553.

[5] Ying Chen et al, ‘Patterns of Symptoms before a Diagnosis of First Episode Psychosis: A Latent Class Analysis of Uk Primary Care Electronic Health Records’ (2019) 17(1) BMC Medicine 227.

[6] Chandra Kiran and Suprakash Chaudhury, ‘Understanding Delusions’ (Pt Medknow Publications) (2009) 18(1) Industrial psychiatry journal 3-18.

[7] R. Caplan, ‘Cognitive Dysfunction and Other Comorbidities | Language and Communication Disorders’ in Philip A. Schwartzkroin (ed), Encyclopedia of Basic Epilepsy Research (Academic Press, 2009) 176-180.

[8] Leo Chiu, ‘Differnetial Diagnosis and Management of Hallucinations.’ (1989) 41(3) Jurnal of the Hong Kong Medical Association 292-7.

[9] in NSW this is currently the Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW).

[10] Peter M. Haddad and Christoph U. Correll, ‘The Acute Efficacy of Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia: A Review of Recent Meta-Analyses’ (Pt SAGE Publications) (2018) 8(11) Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology 303-318.

[11] Richard Whale et al, ‘Effectiveness of Antipsychotics Used in First-Episode Psychosis: A Naturalistic Cohort Study’ (Pt The Royal College of Psychiatrists) (2016) 2(5) BJPsych open 323-329.

[12] Haddad and Correll, ‘The Acute Efficacy of Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia: A Review of Recent Meta-Analyses’ (n 9)

[13] Kenneth S. Kendler, ‘The Development of Kraepelin’s Concept of Dementia Praecox: A Close Reading of Relevant Texts’ (2020) 77(11) JAMA Psychiatry 1181-1187.

[14] John Gilmore, ‘Understanding What Causes Schizophrenia: A Developmental Perspective’ (2010) The American Journal of Psychiatry Online.

[15] DR Weinberger, ‘Implications of Normal Brain Development for the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia.’ (1987) 44 Arch Gen Psychaitry 660-669.

[16] PA Ringen et al, ‘Differences in Prevalence and Patterns of Substance Use in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder’ (2008) 38(9) Psychological Medicine 1241-1249.

[17] Marc Manseau and Michael Bogenschutz, ‘Substance Use Disorders and Schizophrenia’ (2016) 14(3) Focus Psychiatry Online 333-342.

[18] Carolyn J. Asher and Linda Gask, ‘Reasons for Illicit Drug Use in People with Schizophrenia: Qualitative Study’ (2010) 10(1) BMC Psychiatry 94.

[19] PhD Dr Carsten Hjorthøj et al, ‘Years of Potential Life Lost and Life Expectancy in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’ (2017) 4(4) The Lancet 295-301.

[20] Ibid.

[21][21] Antti Alaräisänen et al, ‘Suicide Rate in Schizophrenia in the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort’ (2009) 44(12) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 1107-1110.

[22] Preben Bo Mortensen and Knud Juel, ‘Mortality and Causes of Death in First Admitted Schizophrenic Patients’ (1993) 163(2) The British Journal of Psychiatry 183-189.

[23] P Allebeck et al, ‘Are Suicide Trends among the Young Reversing? Age, Period and Cohort Analyses of Suicide Rates in Sweden’ (1996) 93(1) Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 43-48.

[24] Australian Institute of Health Welfare, ‘The Definition and Prevalence of Intellectual Disability in Australia’ (Canberra No DIS 2, AIHW, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/definition-prevalence-intellectual-disability-au>.

[25] H. Verdoux et al, ‘Suicidality and Substance Misuse in First-Admitted Subjects with Psychotic Disorder’ (1999) 100(5) (1999/11/24) Acta Psychiatr Scand 389-95.; E. Walsh et al, ‘Prevalence and Predictors of Parasuicide in Chronic Psychosis’ (Pt John Wiley & Sons, Ltd) (1999) 100(5) Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 375-382.

[26] Stacy Shaw Welch, ‘A Review of the Literature on the Epidemiology of Parasuicide in the General Population’ (2001) 52(3) Psychiatric Services 368-375.

[27] Ibid.

[28] David PJ Osborn et al, ‘Relative Risk of Cardiovascular and Cancer Mortality in People with Severe Mental Illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Research Database’ (2007) 64(2) Archives of general psychiatry 242-249.

[29] Mortensen and Juel, ‘Mortality and Causes of Death in First Admitted Schizophrenic Patients’ (n 21)

[30] Siow-Ann Chong et al, ‘Mortality Rates among Patients with Schizophrenia and Tardive Dyskinesia’ (2009) 29(1) Journal of clinical psychopharmacology 5-8.

[31] Madhouses Act 1774 14 Geo. III c 49.

[32] County Asylums Act 1808 48 Geo. III, c. 96, s.26.

[33] County Asylums Act 1828 9 Geo IV, c. 40, s.51.

[34] Lunacy Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c.100.

[35] Renee Fabian, ‘The History of Inhumane Mental Health Treatments’, The Talkspace Voice (Blog Post or Webpage, 31/7/2017) <https://www.talkspace.com/blog/history-inhumane-mental-health-treatments/>.

[36] Tanya Lewis, ‘Lobotomy: Definition, Procedure and History’, Live Science (Blog Post or Webpage, 16/10/2021) <https://www.livescience.com/42199-lobotomy-definition.html>.

[37] Thomas A. Ban, ‘Fifty Years Chlorpromazine: A Historical Perspective’ (Pt Dove Medical Press) (2007) 3(4) Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 495-500.

[38] W. W. Shen, ‘A History of Antipsychotic Drug Development’ (1999) 40(6) (1999/12/01) Compr Psychiatry 407-14.

[39] Inquiry into Health Services for the Psychiatrically Ill and Developmentally Disabled. The Richmond Report, March 1983).

[40] National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth).

[41] s 3 ibid.

[42] Registered under Part 3 ibid.

[43] Matthew Doran, ‘National Disability Insurance Scheme Review Reveals Many Have ‘Frustrations’ with the Bureaucracy’, ABC News (Blog Post or Webpage, 20/01/2020) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-20/ndis-report-details-frustration-and-poor-experiences-with-staff/11881312>.

[44] Nicola Hancock and Jennifer Smith-Merry, ‘It’s Hard for People with Severe Mental Illness to Get in the Ndis – and the Problems Don’t Stop There’, The Conversation (Blog Post or Webpage, 21/01/2020) <https://theconversation.com/its-hard-for-people-with-severe-mental-illness-to-get-in-the-ndis-and-the-problems-dont-stop-there-130198>.