WWI, WWII and the Origin of Internal Security Agencies

Table of Contents

World War I

During World War I and World War II executive prerogative overshadowed consideration of any application of fundamental legal rights. The War Precautions Act 1914 allowed the Governor-General to make regulations for securing the public safety and defence of the Commonwealth.[1] It also allowed, inter alia, for the ‘Courts-Martial and punishment of persons . . . communicating with the enemy’ or who ‘spread reports likely to cause disaffection or alarm’.[2] The power of courts-martial was not restricted to members of the military, it allowed for any person who breached the regulations to be treated as if they were a member of the military.[3] The Defence Act 1903 incorporated, so far as they were not inconsistent, the powers of courts-martial in the ‘King’s Regular Forces’.[4] The Unlawful Associations Act 1916 was also introduced ‘for the duration of the present war and a period of six months thereafter, but no longer’.[5] It made unlawful the Industrial Workers of the World and ‘any association which, by its constitution or propaganda, advocates or encourages, or incites or instigates to, the taking or endangering of human life, or the destruction or injury of property’.[6] It also introduced a penalty of six months imprisonment for advocating or inciting a crime,[7] the same period of imprisonment for members of an unlawful association advocating or inciting to acts impeding warlike preparations,[8]and six months imprisonment for printing or publishing matter inciting a crime.[9] If a person committed an offence under the Act and was ‘not . . . a natural-born British subject born in Australia’, then after serving the term of imprisonment deportation was an option.[10]

World War II

The National Security Act 1939 gave broad powers to the Governor-General to ‘make regulations for securing the public safety and defence of the Commonwealth’ during the Second World War with Germany.[11] The Act had an emphasis on control of aliens and shifted the onus of proof onto the individual to prove he or she was not an alien.[12] The Act was later amended by the National Security Act 1939-1940. The regulations section allowed the making of very broad regulations.[13] On 15 June 1940 the National Security (Subversive Associations) Regulations were used to declare the Communist Party of Australia along with a few other organisations and individuals unlawful. In the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, No 110 the Governor-General, Alexander Gore Arkwright, Baron Gowrie declared the Communist Party of Australia ‘prejudicial to the defence of the Commonwealth or the efficient prosecution of the war’. This declaration was revoked by the Governor-General in Council on 18 December 1942. The fact that the Soviet Union had entered the war may have been a significant factor in revoking the unlawful status, however, within the Commonwealth Investigations Branch its Director placed emphasis on undertakings given by the Communist Party leadership to support the war effort. He wrote to the Inspector-in Charge of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch in Perth, forwarding a ‘copy of undertaking signed by J.B. Miles, L.L. Sharkey and eleven other persons that, in consideration of the setting aside of the Order dated 15th June, 1940, declaring the Communist Party of Australia to be unlawful, they will observe the requirements of the National Security Act and the Regulations and Orders’ and that if ‘maximum support for the war effort was not observed, the ban would be re-imposed’.[14]

Attempts to Outlaw the Communist Party Post World War II

The introduction of restrictive legislation during war time may be able to be justified on the basis that the nation is under threat to the extent that it needs to act quickly in self defence, and that extraordinary actions may be needed to meet immediate dangers. Part of this reasoning, which amongst other things provides a basis for the exercise of executive prerogative, is the proposition that normal law enforcement methods are insufficient, and actions taken in self defence may have to break domestic laws and breach of fundamental legal rights. Similar arguments are promoted in peace time when governments want to ban groups and limit or remove fundamental legal rights.

Breaking the Coal Miners Strike

Probably the first major intervention by the executive arm of government that attacked not only the activities of the Communist Party of Australia but also trade unions and their activities was when Labor Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, engaged in breaking a coal miners’ strike in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales in 1949. Chifley used the army to break the strike, and had parliament pass the National Emergency (Coal Strike) Act 1949. The National Emergency (Coal Strike) Act 1949 section 4 made it unlawful on penalty of one thousand pounds for ‘a participating organization . . . [to] make, or promise to make, any payment for the purpose of assisting or encouraging, directly or indirectly, the continuance of the strike’; section 5 made it, on penalty of six months imprisonment or fines, illegal to ‘receive a payment or benefit from any person for the purpose of assisting or encouraging, directly or indirectly, the continuance of the strike’. The strike was broken within seven weeks, but the use of the military probably did not enhance Chifley’s standing in the electorate because he lost the next federal election. The legal basis for the use of the military to break a strike is moot.[15] Whether arguable or not, the Australian government used troops to defeat strikes a number of times in the 20th Century. Intervention by the military in the Waterfront dispute at Bowen 1953, the Qantas Strike 1971, and the use of the RAAF during the 1989 Airline Pilots’ Dispute are examples.[16] The use of the army in Hunter Valley coal fields’ disputes also has precedents. On Sunday 21 September 1879, the New South Wales Permanent Artillery were used for a 95 day occupation of parts of the Newcastle coalfields,[17] and in 1888, during a three months strike in the coalfields, 200 soldiers were used to assist strike breakers.[18]

Chifley was assisted by the Commonwealth Investigation Service (CIS), to gather information about the strike. David Horner in his official history of the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation makes brief reference to the role played by the CIS. He states: ‘In July the CIS, with police assistance, raided the ACP headquarters, Marx House, at 695 George Street, Sydney and other communist establishments, seizing documents’.[19] Horner does not make reference to the contents of the documents seized or their worth. This is a striking oversight for an official history that includes a lot of details about meetings and reasons why ASIO was established, yet one of its main activities receives only a short mention. It is assumed that, because Horner had access to the ‘ASIO data base’,[20]any documents that were seized that showed a threat to the State at the time would have been referred to, and reference made to the value of such raids to State security, or at least used to provide another reason why the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation needed to be established. The use of the CIS was a portend of what was to come when the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation was established.

The leader of the opposition in federal parliament Robert Menzies in his 1949 election speech railed against socialism and specifically promised to outlaw the Communist Party. It was not a false promise, and his use of fear to gain support engaged with past approaches and was to be emulated by future politicians whenever they wanted to ban groups and restrict rights. Menzies described Communism in Australia as ‘an alien and destructive pest’ that acted in the interests of a foreign power, and that it engaged in ‘a series of damaging industrial disturbances with no true industrial foundation’.[21]

Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 was passed on 19 October 1950 and received the Governor-General’s assent the next day. It contained nine recitals six of which referred to the Australian Communist Party. The fourth recital claimed, ‘the Australian Communist Party, in accordance with the basic theory of communism, as expounded by Marx and Lenin, engages in activities or operations designed to assist or accelerate the coming of a revolutionary situation, in which the Australian Communist Party, acting as a revolutionary minority, would be able to seize power and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat’. The fifth recital contended that ‘the Australian Communist Party also engages in activities or operations designed to bring about the overthrow or dislocation of the established system of government of Australia and the attainment of economic, industrial or political ends by force, violence, intimidation or fraudulent practices’. The sixth said that ‘the Australian Communist Party is an integral part of the world communist revolutionary movement, which, in the King’s dominions and elsewhere, engages in espionage and sabotage and in activities or operations of a treasonable or subversive nature’. The seventh said that ‘certain industries are vital to the security and defence of Australia (including the coal-mining industry, the iron and steel industry, the engineering industry, the building industry, the transport industry and the power industry)’. The eight linked with the seventh recital claiming, ‘the Australian Communist Party, and activities or operations of, or encouraged by, members or officers of that party and other persons who are communists, are designed to cause, by means of strikes or stoppages of work, and have, by those means, caused, dislocation, disruption or retardation of production or work in those vital industries’. The final recital indicated that the Australian Communist Party and ‘bodies of persons’ affiliated with it ‘should be dissolved’, and property ‘forfeited to the Commonwealth’. Additionally, it said ‘that members and officers of that party or of any of those bodies and other persons who are communists should be disqualified from employment by the Commonwealth and from holding office in an industrial organization’.

The Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 was passed on 19 October 1950 and received the Governor-General’s assent the next day. It contained nine recitals six of which referred to the Australian Communist Party. The fourth recital claimed, ‘the Australian Communist Party, in accordance with the basic theory of communism, as expounded by Marx and Lenin, engages in activities or operations designed to assist or accelerate the coming of a revolutionary situation, in which the Australian Communist Party, acting as a revolutionary minority, would be able to seize power and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat’. The fifth recital contended that ‘the Australian Communist Party also engages in activities or operations designed to bring about the overthrow or dislocation of the established system of government of Australia and the attainment of economic, industrial or political ends by force, violence, intimidation or fraudulent practices’. The sixth said that ‘the Australian Communist Party is an integral part of the world communist revolutionary movement, which, in the King’s dominions and elsewhere, engages in espionage and sabotage and in activities or operations of a treasonable or subversive nature’. The seventh said that ‘certain industries are vital to the security and defence of Australia (including the coal-mining industry, the iron and steel industry, the engineering industry, the building industry, the transport industry and the power industry)’. The eight linked with the seventh recital claiming, ‘the Australian Communist Party, and activities or operations of, or encouraged by, members or officers of that party and other persons who are communists, are designed to cause, by means of strikes or stoppages of work, and have, by those means, caused, dislocation, disruption or retardation of production or work in those vital industries’. The final recital indicated that the Australian Communist Party and ‘bodies of persons’ affiliated with it ‘should be dissolved’, and property ‘forfeited to the Commonwealth’. Additionally, it said ‘that members and officers of that party or of any of those bodies and other persons who are communists should be disqualified from employment by the Commonwealth and from holding office in an industrial organization’.

Section 4 of the Act declared the Communist Party of Australia an unlawful association and dissolved it. Section 5 allowed for affiliated organisations to be declared unlawful. Section 6 allowed for affiliated organisations to be dissolved. Section 7 provided for 5 years imprisonment for office bearers or members who promoted an unlawful association, to the extent that wearing anything that indicated membership was a crime.[22] Section 8 allowed for the seizing of property. Section 9 allowed the Governor-General to declare a person a communist. Section 10 provided that a person who had been declared could not be employed by the Commonwealth, hold office as a member of a body corporate or hold office in an industrial organisation. It also allowed the Governor-General to declare an industrial organisation. Sections 11 and 12 dealt with suspension from employment and the vacation of office in industrial organisations. Appeals were allowed but the onus of proof shifted to the applicant and this effectively diminished the right to silence by shifting the burden of proof. Section 9(5) stated:

At the hearing of the application, the applicant shall begin; if he gives evidence in person, the burden shall be upon the Commonwealth to prove that he is a person to whom this section applies, but if he does not give evidence in person, the burden shall be upon him to prove that he is not a person to whom this section applies.

The declaration of a person or organisation was to be done without hearing from the person or representatives of the organisation. If an appeal was lodged there was no presumption of innocence and the onus of proof was on the applicant. The Act had striking similarities to anti-terrorism legislation introduced by governments over sixty years later. Communists were to be followed decades later by terrorists; and their existence used to provoke fear and gain public support for draconian legislation. The communists and their sympathisers of the 1950s, if Menzies is to be believed, meet the definition of terrorists[23] under anti-terrorism legislation introduced since 2001. The obvious consequence for many hundreds if not thousands of people, if the Communist Party and its membership level still existed, would be prosecution, conviction and imprisonment.

Media Response to Outlawing Attempt

The media response to the attempt to outlaw the Communist Party of Australia and affiliated organisations is shown by the editorial of The Sydney Morning Herald on Friday 28 April 1950. Under the heading ‘New Bill a Death-Blow to Communist Power’ the endorsement for the abolition of the Party was given:

The attack made on the Communist organisation and its auxiliaries is bold, frontal, and unequivocal. The methods adopted will excite worldwide interest, all the more so because their selection had to have regard for the constitutional limitations upon the power of the Commonwealth Parliament. The moral and political justification for the measure is stated in its “recitals”- a series of devastating and unanswerable propositions, indicating the Communist conspiracy. And this indictment was driven home by Mr. Menzies in a speech memorable for its logical and analytical eloquence.

Response of High Court

The ‘analytical eloquence’ of Menzies and the ‘moral and political justification’ in the recitals were not sufficient for the High Court of Australia, and it declared the Act invalid on the basis that it was beyond the power of the Parliament to use defence powers to suppress organisations and remove civil liberties in a time of peace. The High Court, with only the Chief Justice Latham dissenting, provided a variety of reasons for coming to its ultimate conclusion. Dixon J. stressed at considerable length that the federal government had the power in war time to engage in a way that best allowed the prosecution of the war, but that there was no war being prosecuted that required the defence of the nation and thus the application of defence powers as provided in the constitution. He stated, inter alia:

A war of any magnitude now imposes upon the Government the necessity of organizing the resources of the nation in men and materials, of controlling the economy of the country, of employing the full strength of the nation and co-ordinating its use, of raising, equipping and maintaining forces on a scale formerly unknown and of exercising the ultimate authority in all that the conduct of hostilities implies. These necessities make it imperative that the defence power should provide a source whence the Government may draw authority over an immense field and a most ample discretion. But they are necessities that cannot exist in the same form in a period of ostensible peace. Whatever dangers are experienced in such a period and however well-founded apprehensions of danger may prove, it is difficult to see how they could give rise to the same kind of necessities. The Federal nature of the Constitution is not lost during a perilous war. If it is obscured, the Federal form of government must come into full view when the war ends and is wound up. The factors which give such a wide scope to the defence power in a desperate conflict are for the most part wanting.[24]

The High Court decision did not halt the government from continuing its attempt to ban the Communist Party.

The Referendum

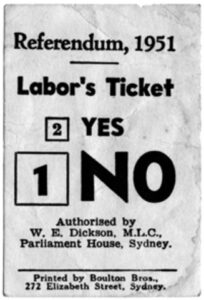

The issue was put to a constitutional referendum on 22 September 1951. The aim was to add a new section 51A to the Constitution. The question posed was: ‘Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled “Constitution Alteration (Powers to deal with Communists and Communism) 1951”?’

The issue was put to a constitutional referendum on 22 September 1951. The aim was to add a new section 51A to the Constitution. The question posed was: ‘Do you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled “Constitution Alteration (Powers to deal with Communists and Communism) 1951”?’

The Constitutional amendment was not carried by the voters. It was rejected on both requirements contained in section 128 of the Australian Constitution.[25] Only 49.44% of the National Vote approved the proposed change and it was carried in only three States: Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania.

The legislation would have allowed decisions about individuals and organisations to have been made in secret, reverse the onus of proof, and remove the presumption of innocence. It was rejected by the Australian people, but by a margin of only 52,000 votes. The electorate’s inherent conservatism rather than the campaigning skills of the Deputy Leader of the Opposition, Evatt, may well have been the reason why the affront to fundamental legal rights was rejected. There have been 44 referendum questions put to the Australian people and only 8 have been carried.[26]

Use of Security Services

The Commonwealth Investigation Service had been used by Chifley to assist with breaking the coal miners’ strike in 1949. Menzies also used a security agency to assist him to try and defeat a domestic non-government organisation he disliked, and to gain political advantage. In Menzies’ case he used ASIO in a political way that had been specifically excluded when it was established. The Directive from Chifley that established ASIO in 1949 contained a specific reference to the requirement that it ‘be kept absolutely free from any political bias or influence, and that nothing should be done that might lend colour to any suggestion that it is concerned with the interest of any particular sections of the community’.[27] This requirement was shortly to be interpreted as not relevant to the Menzies’ Government’s attempt to ban the Communist Party in 1951. In fact, ASIO played a significant role in supporting the government’s campaign to outlaw the Communist Party. David Horner notes that ‘ASIO was closely involved in drafting the preamble to the bill.’[28] As part of its support of the campaign, ASIO provided Prime Minister Menzies with a list of 53 Australian trade unionists that it was said were communists. The information was contained in ASIO Bulletin No.2 dated 1 March 1950. Menzies read out the list of names supplied by ASIO which contained a number of inaccuracies.[29] The use of ASIO for political purposes remains an issue, especially in light of its history of surveillance of citizens and non-government organisations and its greatly increased powers in the 21st Century.

When trying to evaluate the reasons for the development and derogation of legal rights, there is necessarily a bias in the contemporary interpreter created by cultural conditioning. At the centre of historical consciousness should be the awareness that everything is relative or related to the context in which it arose or in which it exists.[30] The application of hermeneutics is not easily done. However, there is an objective reality that transcends the centuries: those who have power maintain and accrue to themselves control over others – if permitted. The impact on the individual, while varying in degree, is usually the same, death or the removal of liberty. The legislative restrictions imposed on the liberty of the individual over the past 200 years in Australia, so far as they derogate fundamental legal rights, have no evidential basis justifying removal or limitation of the rights. For example, the fact that the Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950 could not be used has had no adverse consequences for Australia. The community did not need protection from Australian communists as claimed by Menzies, and there had been no overt actions that could be used to substantiate the Act.

Proof of need for the removal of rights in order to ensure the safety of individuals or the society as a whole has not been a necessary condition for the removal of rights, or for the establishment of agencies that have as part of their function the invasion of privacy and the derogation of rights. In Australia the main agency that has been used by politicians to erode freedoms is the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation.

Establishment and Function of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

Prior to the establishment of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation in 1949 the first example of a security intelligence service was the Prime Minister’s Special Intelligence Bureau created in 1916. In 1915, the British government arranged for the establishment of a Commonwealth branch of the Imperial Counter Espionage Bureau in Australia. This branch, known as the Australian Special Intelligence Bureau (SIB) was established in January 1916. The SIB maintained a close relationship with state police forces, and later with the Commonwealth Police Force. The Commonwealth Police Force was created in 1917 under the War Precautions Regulations to conduct investigations independent of state police forces. In 1919, the Commonwealth Police and the Special Intelligence Bureau merged to form the Investigation Branch within the Attorney General’s Department. The Bureau was formally established by Executive Council Minute on 14 February 1917. State Chiefs of Police were ex-officio members of the Special Investigation Bureau. The paramount concern during the war and those years leading up to it was espionage and sabotage. David Horner starts his work on the history of ASIO by describing the activities of the German Commercial Attache, Walter de Haas, who was attached to the German Consul-General’s office in Sydney. Haas’ trips in 1911 to Thursday Island and Darwin apparently attracted attention and surveillance by local police.[31] During the war the Army’s Directorate of Intelligence had a number of tasks, including the surveillance of enemy aliens.[32] Horner describes the reaction to the fear of espionage and sabotage:

Foreign nationals, mainly Germans, were rounded up and placed in internment camps. Walter de Haas and several businessmen who were German spies were among the interned aliens. Meanwhile, concerned members of the public were on the alert for incidents such as possible spies signalling by lights to enemy ships offshore.[33]

Similar concerns about espionage and sabotage existed during World War II. The Special Investigation Bureau was responsible for internal security up to the end of World War II. After the war, in 1946, the Investigation Branch was re-organised and renamed the Commonwealth Investigation Service (CIS). The focus changed after the World War II to Australian citizens who did not have faith in the capitalist system.

The establishment of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, according to Horner, was as a direct result of America and Britain outing Australia from ‘Allied Sigint’, based on the belief that there were Australians in government departments spying for the Soviet Union.[34] On 16 March 1949, Labor Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, issued a ‘Directive for the Establishment and Maintainance (sic) of a Security Service’. The Directive came in the form of a memorandum to ‘The Director General of Security’ classified as ‘secret’ and not declassified until 1976.[35] The memorandum was the method used to initiate the establishment and maintenance of a Security Service[36] and to appoint a Director General of that service. The Security Service formed part of the Attorney General’s Department and the Attorney General was responsible to Parliament for it.[37] The secret nature of the Directive and the Security Service meant that it effectively had no parliamentary oversight and its operations were unknown to parliamentarians and the public.

The Director General was given direct access ‘at all times’ to the Prime Minister.[38] The extent of ministerial involvement was limited in the following terms, ‘It is your [Director General] responsibility to keep each Minister informed of all matters affecting security coming to your knowledge and which fall within the scope of his Department’.[39] In case there was any doubt about the limited extent of ministerial involvement, Prime Minister Chifley stressed to the Director General,

You and your staff will maintain the well established convention whereby Ministers do not concern themselves with the detailed information which may be obtained by the Security Service in particular cases, but are furnished with such information only as may be necessary for the determination of the issue.[40]

The function of the Security Service was described in the following terms.

The Security Service is part of the Defence Forces of the Commonwealth and save as herein expressed has no concern with the enforcement of the criminal law. Its task is the defence of the Commonwealth from external and internal dangers arising from attempts at espionage and sabotage, or from within or without the country, which may be judged to be subversive of the security of the Commonwealth.[41]

There is no definition in the Directive for ‘subversive’, but for the purpose of the Directive and the subsequent Charter and legislation the description provided by Royal Commissioner Hope is probably apt, in the sense of acceptable to those promoting the need for a secret security organisation: ‘Subversion, which is activity whose purpose is ultimately, to overthrow constitutional government, and in the meantime to weaken or to undermine it’.[42]

Hope later in his report qualifies the definition of subversion, stating:

Subversion is difficult to define but is nonetheless a very real, and may be a very dangerous, form of activity. In para 35 I described rather than defined it as an activity whose purpose is, directly or ultimately, the overthrowing of the constitutional government, and in the meantime the weakening or undermining it. “Overthrowing the government” does not, of course, refer to the ousting by constitutional methods of the political party in power for the time being but the overthrow by unconstitutional methods of the established constitutional government or system of government.[43]

The concern about how such an organisation might be used to undermine civil liberties and potentially advance the interests of the government of the day seems to be reflected in the emphasis placed on the defence of the Commonwealth and the limitation of the activities for this purpose. Chifley’s Directive stressed the requirement that the organisation be kept free of political bias or influence. It contained the following instructions to the Director General:

You will take especial care to ensure that the work of the Security Service is strictly limited to what is necessary for the purpose of this task and that you are fully aware of the extent of its activities. It is essential that the Security Service should be kept absolutely free from any political bias or influence, and nothing should be done that might lend colour to any suggestion that it is concerned with the interests of any particular section of the community, or with any matters other than the defence of the Commonwealth. You will impress on your staff that they have no connection whatever with any matters of a party political character and that they must be scrupulous to avoid any action which could be so construed.[44]

Nothing in the Directive, apart from the instruction about political bias, provided guidelines about how the Security Service should go about its work or what limits there were as long as the activities fell under the umbrella of ‘espionage’, ‘sabotage’ and ‘subversion’. The requirement for the activities to be in defence of the Commonwealth gave it Constitutional validity pursuant to section 51(vi): ‘The naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth’.

The extent to which Chifley was serious about the Security Service avoiding political bias is unclear from his instruction. As the Security Service grew and became the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation its activities clearly focused on political dissenters, the Australian Communist Party and other parties that did not hold the same fundamental beliefs as the Labor Party, Liberal Party and Country Party.

On 19 December 1949 Robert Menzies again became Prime Minister of Australia: this time as leader of the Liberal Party. On 6 July 1950 he followed in Ben Chifley’s footsteps and issued ‘A directive from the Prime Minister to the Director-General of Security’ under the heading ‘Charter of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation’.[45] The directive was issued to Colonel C.C.F. Spry, Director-General of Security. This directive was also classified as ‘secret’ and not declassified until 1976.The directive informed the Director-General of Security of his duty ‘to direct and maintain the Security Service established under the name of the Australian Security Intelligence Organization.[46] A second directive provided additional detail about how the ‘Organization’ was to function. For example, Menzies added a paragraph about co-operation with other agencies.

For the purposes of the Organization you will establish the maximum co-operation with other agencies, whether of Commonwealth or of the States, operating in the field of security (and, where appropriate, in the field of law-enforcement) in Australia, and will maintain effective contact with appropriate security agencies in other countries.[47]

Apart from some minor changes, the Menzies Charter mirrored Chifley’s Charter and did not provide many guidelines about how the Organization should conduct itself. The creation of ASIO without parliamentary oversight and enforceable guidelines remains a feature to the present day in that any parliamentary involvement is strictly limited to the extent that it is virtually meaningless,[48] despite legislative changes that have expanded its powers. The Charters had no legislative basis and have been tactfully described as, ‘more a statement of principles of activity than a document of incorporation or authority’, creating ‘together with relevant minutes of the Federal Executive Council, the only authority for ASIO’s existence and operations until 13 December 1956, when ASIO was established by statute.’[49]

The Charters were followed by legislation, assented to on 15 November 1956, which placed the Chifley and Menzies Charters in statutory form and provided some operational clarity. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1956 section 4(1) and (2) of the Act stated:

The Australian Security Intelligence Organization, being the Organization established in pursuance of a directive given by the Prime Minister on the sixteenth day of March, One thousand nine hundred and forty-nine, is, subject to this Act, continued in existence.

The Organization shall be under the control of the Director-General.

The functions of the Organisation were contained in section 5. The functions section provided the Director-General with broad powers in the same way as allowed by the Charters; and it specifically excluded ASIO from having enforcement powers: something that was to change in the 21st century. Section 5(a) directed the Organisation ‘to obtain, correlate and evaluate intelligence relevant to security and, at the discretion of the Director-General, to communicate any such intelligence to such persons, and in such manner, as the Director-General considers to be in the interests of security’. Section 5(b) gave the Director-General the discretionary power to advise Ministers ‘in respect of matters relevant to security, in so far as those matters relate to Departments of State administered by them.’

The justification for the establishment of ASIO was said to have been because the Commonwealth Investigation Service that was fulfilling security needs was ‘found wanting’ and the ‘UK Security Service had very strongly urged Mr Chifley to set up a new service’.[50]

John Burton, the Secretary of the Department of External Affairs from 1947 to 1950, noted that with the advent of the Cold War the subservience of Australia to it powerful allies was entrenched, and a more open foreign policy thwarted, with intelligence agencies playing an active part in this outcome. He stated:

The recognition of communist China was high on the agenda, but finally frustrated by the beginning of Cold War reactions against these policies prior to the 1949 elections.

Post-war reconstruction dreaming then came to an end. In the following years, Australian Labor’s policy was quickly subverted by American and British so-called ‘Intelligence’, and subsequently by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Defence Department, whose members could conceive of Australian security only in pre-war power balance terms, and pre-war reliance on, subservience to the United Kingdom and the United States of America.[51]

The emphasis on secrecy as an integral part of security activities and the lack of accountability has, no doubt, facilitated the growth of organisations such as ASIO. Burton comments on the reason for such secrecy in a diplomatic context and dismisses it as rarely warranted. He says: ‘Foreign offices around the world retain secrecy primarily to give status, to hide error and a lack of information and policy’.[52] The use of secrecy in a domestic context to cloak the activities of ASIO may also give it a status it does not deserve. However, Burton’s advocacy, according to Horner, was one of the four reasons why Chifley decided to create ASIO.

Chifley had agreed to establish a new security organisation for several reasons. First, he had been briefed on the Venona program. Second, Hollis was able to show that Milner and Bernie had most likely passed classified information to the Soviet Embassy. Third, Burton had persuaded Chifley about the importance of security in the context of Australia’s role in the British Commonwealth and Empire. Fourth, it was becoming apparent that the continual denial of access to US information would be damaging to Australian defence.[53]

British Nuclear Tests in Australia

The desire to be part of the western security system was apparently too enticing. However, the emphasis was still on security within the public service and on foreign powers, rather than on Australian citizens. The change to a focus on Australian citizens increased as Australia became more involved in British and American activities. The Long Range Weapons Establishment at Woomera and the British Nuclear Tests in Australia were good examples of how ASIO could be used by politicians who wished to keep secret the extent of their dangerous activities. Horner briefly notes the importance of vetting people for these projects:

One of the most important tasks was the vetting of all people, including employees of private firms, who were employed at the Woomera Rocket Range, and later Maralinga; the checking of employees at Radium Hill; and later again, in collaboration with the Department of Supply, the complete coverage of people with access to, and knowledge of, atomic explosions in the north-west of Australia.[54]

In the case of the British Nuclear Tests in Australia, the Menzies Liberal Government, and the Opposition Labor Party, were eager to have nuclear testing in Australia. Alan Parkinson provides a history of the nuclear testing program at the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia, and Emu and Maralinga in South Australia.[55] There were 12 major atomic explosions between 3 October 1952 and 9 October 1957 and a series of trials involving plutonium through to 1963. Parkinson notes that there were 24,400g of plutonium used and only 900g were repatriated to Britain.[56] The testing program exposed Aboriginals to fallout from the major tests and to plutonium from the later trials, and they were also forced off their land; Australian servicemen were exposed to fallout as they watched the tests and later cleaned planes and other machinery; and segments of the Australian population were polluted with fallout as it drifted from the South Australian test sites over parts of eastern Australia. The suppression of information about what occurred was assisted by ASIO and continued until the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia was initiated in 1984.

The Hope Inquiry

The justification for the existence of ASIO was provided in 1976 by Royal Commissioner Hope, who produced reports that provided general propositions about how necessary such an organisation was, and based his conclusions on assumptions rather than evidence that could be evaluated by others. He concluded:

I find, therefore, that Australia needs a security intelligence organisation like ASIO. The proper fields for investigation by ASIO should, however, be more clearly defined than in the present ASIO Act. They should include:

- Espionage.

- “Active measures”.

- Subversion.

- Sabotage.

- Terrorism (politically motivated violence)

- Domestic activity related to violence and subversion abroad.[57]

The requirement for secrecy by Australia’s main allies if intelligence sharing was to take place was a factor from the beginning and remains so to the today, even if the main enemy is no longer the Soviet Union. What is striking is that there has never been evidence produced to show the effectiveness of the organisation in countering the perceived threats listed by Royal Commissioner Hope: no matter how much time passes evidence is not provided and the acceptance of the need for such an organisation remains primarily based on faith rather than proof. For example, the concern with subversion is highlighted in the Charters and by Royal Commissioner Hope, and there existed in the Crimes Act 1914 from 1920 until 2005[58] the offence of sedition which is the subversion of political authority.[59] Prosecutions for sedition in the 20th Century in Australia have involved only a few cases. In Burns v Ransley[60] the High Court dismissed the conviction; in R v Sharkey[61] the High Court upheld the conviction; and in Sweeney v Chandler[62] the charge was dismissed in the Court of Petty Sessions. The cases involved public utterances that did not require a security organisation to identify. Subversive activities could also potentially result in a prosecution for treason which carried the death penalty when introduced in the Crimes Act 1914.[63] There have been no prosecutions for treason. There is the notable Petrov case that involved a Royal Commission in 1954, but no criminal prosecutions resulted. There have also been no prosecutions for sabotage.

Australian Security Intelligence Organization Act 1979

The 1956 Act was followed by the Australian Security Intelligence Organization Act 1979. This Act significantly expanded the procedural and operational sections, whilst maintaining the functions as previously enacted. Section 17 of the Act governed functions, stating:

17. (1) The functions of the Organization are-

(a) to obtain, correlate and evaluate intelligence relevant to security;

(b) for purposes relevant to security and not otherwise, to communicate any such intelligence to such persons, and in such manner, as are appropriate to those purposes; and

(c) to advise Ministers and authorities of the Commonwealth in respect of matters relating to security, in so far as those matters are relevant to their functions and responsibilities.

(2) It is not a function of the Organization to carry out or enforce measures for security within an authority of the Commonwealth.

The Act introduced sections relating to search warrants,[64] listening devices,[65] inspection of postal articles[66] and procedural sections relevant to those sections. It also introduced a section relating to security assessments. Section 37 of the Act linked the functions subsection 17(1)(c) to security assessment. It allowed the Organisation to provide security assessments to Commonwealth agencies ‘relevant to their functions and responsibilities’.

Section 38 allowed an individual who received an adverse or qualified assessment to be provided with details of it. However, section 37 allowed reasons for an adverse assessment to be withheld. Section 38 allowed the Director-General to exercise his discretion and decide to withhold the provision of notice of an adverse assessment to an individual.

Section 54 of the Act provided for a Tribunal to review an adverse or qualified assessment. The obvious point about such a review process is that the powers of the Director-General were so broad that the Tribunal could only have a role if he wanted it to have a role and his decision in this regard was not reviewable.

The Act also introduced the requirement that the Director-General provide an annual report to the Minister and the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives about the Organisation’s activities. Section 94 required the Minister to be supplied with a report ‘on the activities of the Organization during that year’, and for the Leader of the Opposition to treat the report as secret.

The content of such reports was to remain unknown because such content was secret, even if there was no basis for secrecy, and presumably the Director-General only included such matters as he considered necessary. Section 8 made clear the overriding power of the Director-General and the limits of the power of the Minister. It placed control of the Organisation with the Director-General and made clear that the Minister was not ‘empowered to override the opinion of the Director-General’ on questions of ‘collection of intelligence’, or communication of intelligence concerning a particular individual’, or ‘concerning the nature of advice that should be given’.[67]

The requirement for candor on the part of the Director-General was absent as was Ministerial or parliamentary control. Section 21 required the Director-General to consult regularly with the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives ‘for the purpose of keeping him informed on matters relating to security’. The section provided no guidance about what ‘matters relating to security’ the Director-General was to inform the Leader of the Opposition about, thus giving a wide discretion to include or not any matters the Director-General deemed appropriate. The discretion given to the Director-General under the 1979 Act remains the same.

Surveillance and Vetting Activities

Examples of the way the Director-Generals of ASIO have used their discretion and extensive powers to engage its security apparatus in surveillance and vetting activities can be found in records eligible for release under the Archives Act 1983. The records relate to the surveillance of individuals, groups and organisations. Since 2010 the access period commences after 20 years. However, there are restrictions, including the fact that the names of those who did the spying, sometimes on their friends and relatives, are not revealed. What the records do show, that was unaccountably not dealt with by Royal Commissioner Hope, is that the spying that took place was a waste of time, money, and, more importantly, involved the invasion of privacy and in numerous instances adversely affected careers. ASIO surveillance on Australian citizens during the Cold War was extensive, and there is no reason to be sanguine that in the 21st Century it is less pervasive or that the current Director-General is any more competent than his predecessors. Indeed, because of the substantial increase in funding it is likely that the surveillance of citizens is on the increase.

A number of stories of ASIO spying are contained in a book edited by Meredith Burgmann titled Dirty Secrets: Our ASIO Files.[68] In the book individuals who accessed their files provide details and point out flaws in the information collected. One person’s story is referred to because she is a well-known Walkley Award winning journalist, and her summary of the ASIO approach can be applied to many other people who suffered under their gaze. Anne Summers AO states:

I have spent a great deal of time reading various other ASIO files on the NAA website and have been quite taken aback by some of what I found. To say that all the stereotypes about ASIO in the 1970s were true is an understatement. ASIO was everywhere, observing, reporting, commenting – often in the most personal way. Even at an anarchist ‘conference’ in Minto, just outside Sydney, in 1971, attended by fewer than forty people. The ASIO agent not only took notes on what was said but made extensive and extremely personal comments about participants, about Paddy McGuinness’s drinking, for instance, and his sister’s ‘illegitimate’ child, about the extent of dope-smoking, even about the way Rosemary Pringle walked. . . . ASIO’s interest in individuals, including me, was exceeded only by its inability to get – or to get right – personal details.[69]

The approach adopted by ASIO agents bears a close resemblance to that of gossip columnists whose aim is to titillate the public with items about celebrities. Michael Tubbs, a respected barrister, in his book ASIO: The Enemy Within,[70]examines his own files and comments more generally on the activities of ASIO. Tubbs makes a number of cogent arguments about worthless ASIO activities, and in respect of the dossier kept on him he makes the point about the unnecessary financial cost to the community:

It is quite clear to me that ASIO has cost the Australian taxpayer, on my dossier alone, much more that I was able to earn myself in those 11 years. I estimate in today’s values the cost would all up have been in the order of $200,000 – $300,000 per year. What did Australian taxpayers get for all their money wasted on me by ASIO? Not a single bloody thing – not a ‘brass razoo’ of public value whatsoever. So what good was it all? How is that for public waste? Yet conservatives yell loud and long about ‘dole cheats’ and the high cost of social security benefits, not enough money for this and not enough for that. What about the waste of taxpayers’ funds by ASIO for no social benefit whatsoever. Thousands of pages and not a single charge laid – what crap![71]

The usefulness of ASIO activities so far as they related to spying and vetting of many thousands of Australian citizens is certainly more than questionable; especially in light of the absence of unlawful activities relevant to national security by those being watched. Whilst vetting and spying on citizens remains a priority, significant changes have occurred to ASIO functions, the most significant happening in the 21st Century.

ASIO’s role has changed from surveillance state activities and a security assessment role to one that engages in a criminal investigative process, albeit in secrecy and without legal rights being an impediment. The legislation has been amended to introduce significant penal provisions where cooperation is not forthcoming. These additional activities provide further potential for abuse of rights and danger to public safety.[72]

The Keating Statement

In July 1992 Labor Prime Minister, Paul Keating announced that the role of ASIO and other agencies had been reviewed as a result of the end of the Cold War. ASIO had sixty people cut from its staff and a budget reduction of $3.81 million. The announcement of the review was in a long, waffling press release that said little and was clearly designed to avoid the suggestion that the government was not concerned about security. The small reductions were to be short lived, with an increased role for ASIO before and during the Sydney Olympics in 2000, and a dramatically expanded role in the 21st Century as part of the preventive ‘war on terror’. While ASIO funding in 1998-99 had returned to the level of 1992-93 of just under $50 million, after 1999 it increased dramatically.[73]

The Keating statement is interesting because it shows that, despite the budget reduction, it was necessary to claim adherence to the security state apparatus and foreign alliances. Keating stated, inter alia:

In the light of the fundamental changes in the world since the end of the Cold War, the Government commissioned earlier this year a review of the overall impact of changes in international circumstances on the roles and priorities of the Australian intelligence agencies and of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade as a provider of reporting.

The review examined how Australia’s interests have been affected by the rapid and significant changes in international circumstances, whether Australia still needs the intelligence structure it has and, if so, whether the roles and priorities of our intelligence agencies need to be adjusted. It also looked at how changes in international circumstances would affect management and coordination arrangements between the Australian intelligence and security agencies, and Australia’s partnership and liaison arrangements.

. . . .

The Government considers that global and regional relationships, freed from the rigidity of the Cold War ideological and strategic divide, will become more complex and diverse. A more fluid international environment will require a sharper appreciation of Australian interests and priorities, of the resources available to pursue our goals, and of the need to allocate those resources effectively.

. . . .

The Government has decided not to alter the basic structure of Australia’s intelligence community which was set in place after Mr Justice Hope’s comprehensive reviews, for

reasons of enduring concern relating to efficiency and effectiveness. Essential to that structure is the separation of the assessment, policy and foreign intelligence collection functions –a philosophy which the Government continues to embrace.

. . . .

The review stresses the need for a self-reliant intelligence capability in those areas and issues of highest priority for Australia, but recognises the benefits which continue to flow to us from the long-standing partnership agreements with the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada. It also recognises the importance of developing and strengthening regional intelligence liaison arrangements.[74]

The review was announced after it occurred, and its terms of reference, the data and assumptions upon which it relied remain hidden. The Hope Royal Commission at least provided some reasoning for the conclusions it reached.

Assault on Derogable Rights

The restriction of fundamental legal rights through the growth of ASIO was confined, so far as can be discerned from publicly available records, to derogable rights. For example, the right to freedom of opinion and expression was undermined with sedition laws that in a number of instances were used to prosecute communists. These laws existed prior to the establishment of ASIO, but its existence was, at least in part, justified on the basis that such laws were necessary. The main assault on derogable rights during the 20th Century can be gleaned from the use of ASIO for surveillance and reporting on the political activities of individuals. Such reporting activities, as is shown by some of those who have accessed their ASIO records, can have an impact on the right to equality and non-discrimination. The main impact, however, derives from the creation of a state where citizens become accustomed to insidious surveillance activities and adopt an attitude that seems to deny the potential for adverse impacts on them: it happens to bad people. The growth of ASIO powers in the 21st Century had its genesis in the 20th Century and, instead of the development of a freer society with the enhancement of legal rights, the reverse has occurred. So far as terrorist activities were concerned the available evidence suggests that ASIO had little interest, at least between 1963 and 1975. John Blaxland notes that, regarding this period, ‘ASIO did not see terrorism as falling within its charter as defined by the ASIO Act 1956’.[75]

Conclusion

The war against Aborigines became quiescent during the first part of the 20th Century, and the focus changed after World War II to the Cold War when attempts were made to outlaw the Communist Party. The 20th Century was marked by the creation and growth of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation which was used as a tool of government against domestic communists. The attempted abrogation of fundamental rights was thwarted by the High Court and the narrow defeat of the 1951 referendum, but with the growth of ASIO the Australian Government gained a powerful tool that it can wield in secret. Such expansion has been achieved in the 21st Century without a review of its role and any consideration of whether the powers it has been given are even needed.

The High Court during the mid-20th Century played a notable role in not being swayed by the extreme and repeated rhetoric of fear during the Cold War that communists were a threat to the nation and needed to be outlawed. The decision of the High Court, in rejecting the government’s attempt to ban the Communist Party, was the last time the Court has acted to reject significant legislation abrogating fundamental legal rights. The impact of the High Court decision and the referendum was to maintain fundamental legal rights during the Cold War when it was claimed that Australia was under imminent threat from external and internal communist forces. The threat of a communist invasion and subversion from within was pitched with great force by the Liberal and Country Party politicians of the day. When compared with the danger posed by terrorist attacks now, the Cold War construction of the communist threat must be regarded as a much greater threat. Yet fundamental legal rights could be maintained during the Cold War even though it was claimed that they should be abrogated for those said to be communists. In the 21st Century not only are rights to be taken from suspected terrorists but also from those who are not even suspects. The threat of terrorist attacks, even if severe, can reasonably be regarded as less significant than the defeat of Australia by hostile forces, yet the derogation of rights is now said to be more essential than was publicly urged by even hardline anti-communists in the 1950s and 1960s.

References

[1] War Precautions Act No.14 of 1914, s. 4.

[2] Ibid s. 4(2)(a)(c).

[3] Ibid s. 4(2).

[4] Defence Act 1903, s. 88.

[5] Unlawful Associations Act 1916, s. 1.

[6] Ibid s. 3.

[7] Ibid s. 4.

[8] Ibid s. 5.

[9] Ibid s. 7.

[10] Ibid s. 6.

[11] National Security Act 1939, s. 5.

[12] Ibid s. 15.

[13] National Security Act 1939, s 5.-(1.) Subject to this section, the Governor-General may make regulations for securing the public safety and the defence of the Commonwealth and the Territories of the Commonwealth, and in particular-

(a) for providing for the apprehension, prosecution, trial or punishment, either in Australia or in any Territory of the Commonwealth, of persons committing offences against this Act;

(b) for authorizing-

(i) the taking of possession or control, on behalf of the Commonwealth, of any property or undertaking; or

(ii) the acquisition, on behalf of the Commonwealth, of any property other than land in Australia;

(c) for prescribing any action to be taken by or with respect to alien enemies, or persons having enemy associations or connexions, with reference to the possession or ownership of their property, the conduct or non-conduct of their trade or business, and their civil rights or obligations; . . . .

[14] H.E. Jones, Director, Commonwealth Investigation Branch, Letter, 1 January 1943.

[15] See Elizabeth Ward, Law & Bills Digest Group, ‘Call Out the Troops: an examination of the legal basis for Australian Defence Force involvement in ‘non-defence’ matters’, Parliamentary Library, Research Paper 8, 1997 – 98.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Rod Noble, ‘The Military, The Miners and Mass Civil Disobedience in the Hunter Valley of NSW, 1879-88’, in James Bennett, Nancy Cushings and Erik Eklund (eds), Radical Newcastle (University of New South Wales Press, 2015) 42.

[18] Ibid 47.

[19] David Horner, The Spy Catchers: The Official History of ASIO 1949-1963 (Allen & Unwin, Vol 1, 2014) 104.

[20] Ibid xvii.

[21] Robert Menzies, Speech, Delivered at Melbourne, Vic, November 10th, 1949, Museum of Australian Democracy.

[22] The recent anti motorcycle gang laws have adopted a similar restriction: see s 173EA Liquor Act 1992 (QLD).

[23] The definition of a ‘terrorist act’ is contained in the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth), section 101.1 ‘(b) the action is done or the threat is made with the intention of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause’.

[24] Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth (“Communist Party case”) [1951] HCA 5, 50, 51; (1951) 83 CLR 1, 202-203.

[25] Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, s128 requires, inter alia:

When a proposed law is submitted to the electors the vote shall be taken in such manner as the Parliament prescribes. But until the qualification of electors of members of the House of Representatives becomes uniform throughout the Commonwealth, only one‑half the electors voting for and against the proposed law shall be counted in any State in which adult suffrage prevails.

And if in a majority of the States a majority of the electors voting approve the proposed law, and if a majority of all the electors voting also approve the proposed law, it shall be presented to the Governor‑General for the Queen’s assent.

[26] George Williams and David Hume, People Power: the history and future of the referendum in Australia (UNSW Press, 2010) 138.

[27] Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security Fourth Report, Volume II, 1976, Appendix 4-A, 5.

[28] David Horner, The Spy Catchers: The Official History of ASIO, 1949-1963 (Allen and Unwin, 2014) 139. Remarkably, a recent Director General of ASIO, David Irvine, claimed that ‘ASIO had nothing to do with the banning per se’ of the Communist Party. See Frank Moorhouse, Australia Under Surveillance, (Vintage Books 2014), p 161.

[29] Horner, n 305 above, 140

[30] Paul Gifford, ‘Religious authority: scripture, tradition, charisma’ in John R. Hinnells (ed), The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion (Routledge, 2010) 400.

[31] David Horner, The Spy Catchers: The Official History of ASIO 1949-1963 (Allen & Unwin, Vol 1, 2014) 11.

[32] Ibid 13.

[33] Ibid 13.

[34] Ibid 53.

[35] Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security, Fourth Report, Volume II, 1976, Appendix 4-A, 1.

[36] Ibid 2, paragraph 1. This Directive has become known as The 1949 Charter of ASIO.

[37] Ibid 2.2.

[38] Ibid 2.3

[39] Ibid 2.4.

[40] Ibid 3.8.

[41] Ibid 2.5.

[42] Justice Hope, Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security, Fourth Report, Volume 1, 1976, 17.35.

[43] Ibid 34.55.

[44] Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security Fourth Report, Volume II, 1976, Appendix 4-A, 1.6.

[45] Ibid, Appendix 4-A, 5.

[46] Ibid 5.1.

[47] Ibid 7.12.

[48] Section 28 of the Intelligence Services Act 2001 creates the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, and s 29 provides for its functions which are heavily curtailed by s 29(3).

[49] Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security, Fourth Report [re Australian Security Intelligence Organisation] Vol 1, 1976, 2.5.

[50] Ibid 1.3.

[51] John Burton, ‘A Human Component: The Failure of the Labor Tradition’, in David Lee and Christopher Waters (eds), Evatt to Evans: The Labor Tradition in Australian Foreign Policy (Allen & Unwin, 1997) 24.

[52] Ibid 31.

[53] David Horner, The Spy Catchers: The Official History of ASIO 1949-1963 (Allen & Unwin, Vol 1, 2014) 78.

[54] Ibid 235.

[55] Alan Parkinson, Maralinga: Australia’s Nuclear Waste Cover-up (ABC Books, 2007); see also Reports of the Royal Commission into Nuclear Tests in Australia.

[56] Ibid 7.

[57] Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security, Fourth Report [re Australian Security Intelligence Organisation] Vol 1, 1976, 67.104.

[58] Crimes Act 1914, s24A.

[59] Australian Law Reform Commission, Fighting Words, Report 104, July 2006, 10.34.

[60] (1949) 79 CLR 101.

[61] (1949) 79 CLR 121

[62] Unreported, Sydney Court of Petty, 8 September 1953.

[63] Crimes Act 1914, s 24.-(1.) Any person who within the Commonwealth or any Territory

(a) instigates any foreigner to make an armed invasion of the Commonwealth or any part of the King’s Dominions, or

(b) assists by any means whatever any public enemy,

shall be guilty of an indictable offence and shall be liable to the punishment

of death.

(2.) Any sentence of death passed on an offender in pursuance of this section shall be carried into execution in accordance with the law of the State or Territory in which the offender is convicted.

[64] Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979, 25.

[65] Ibid 26.

[66] Ibid 27.

[67] Section 8 of the current Act has a similar provision but it specifies that the Director-General is subject to the directions of the Minister, and the Minister can in writing override the opinion of the Director-General.

[68] Meredith Burgmann, Dirty Secrets Our ASIO Files (NewSouth, 2014).

[69] Ibid 82, 83.

[70] Michael Tubbs, ASIO: The Enemy Within (Boolarong Press, 2008).

[71] Ibid 87.

[72] For evidence of the abuse of rights by ASIO before the recent legislative changes, and attempts to counteract that, see Ken Buckley, Buckley’s: Ken Buckley, historian, author and civil libertarian – an autobiography (A & A Book Publishing, 2008), pp 254-61 and 303-306.

[73] See Research Note, Parliamentary Library, Dollars and Sense: trends in ASIO resourcing, no. 44, June 2003, p 2. ASIO numbers subsequently doubled in the seven years from 2006 to 2013; see the interview with ASIO Director General David Irvine in Frank Moorhouse, Australia Under Surveillance (Vintage 2014), p 193.

[74] Statement by the Prime Minister, The Hon P. J Keating MP, Review of Australia’s Intelligence Agencies, Canberra, 21 July 1992.

[75] John Blaxland, The Protest Years: The Official History of ASIO 1963-1975 (Allen &Unwin, Vol II, 2015) 158.