Legal Rights Designed to Protect Against Miscarriage of Justice and Limitations

Table of Contents

The legal rights outlined are particularly important in providing safeguards against abuses by governments and their agents. The fundamental rights, developed over hundreds of years, have been adopted in international treaties. Some of the rights along with the reasons for their existence are detailed to provide an understanding of their importance and fragility.

The rights form a fundamental part of the criminal laws, are significant when courts are determining how the law is applied, are relevant when lawyers both prosecution and defence make submissions to the court about admissibility of evidence. They also need to be taken into account by law enforcement agents when they are investigating and apprehending suspects. A breach of a legal right at any level of the criminal justice system can lead to a miscarriage of justice.

The right to life, the pre-eminent right, is referred to in an historical context because in Australia it can no longer be extinguished by the application of law. The rights that safeguard people from arbitrary detention are often described as substantive or procedural, although it is sometimes difficult to make this distinction. The substantive right to liberty is supported by a number of other substantive rights, such as the right to a fair trial, and procedural and quasi-procedural rights, such as the right to silence, which are necessary for a fair trial.

The rights discussed are found in the common law, statute laws and international treaties. International treaties and conventions play a part in the protection of legal rights, but unless they have been adopted into Australian statutes their influence is often more morally persuasive on courts than legally compelling, depending on the inclination of the particular judges. The rights examined, as with all rights, are subject to the Constitution and can be modified or extinguished by Parliament.

The rights established by the common law have no protection against removal by Parliament, as will be shown, unless the words contained in a statute lack specificity or they offend the powers given to courts by Chapter III of the Constitution which vests judicial power in the High Court, federal courts created by Parliament and State courts that are entrusted with federal jurisdiction. The rights that can be protected by the courts, because they are part of the judicial power provided by Chapter III, are very limited and are implied rather than expressed. Although not closed, the only right currently interpreted as given the protection of Chapter III, and that relates directly to the application of criminal laws, is the right to a fair trial.

International Treaties, Conventions and Fundamental Rights

There are a number of international treaties and conventions that Australia has endorsed that are designed to assist with the protection of fundamental rights against the behaviour of governments that want unfettered powers. The fundamental rights are given protection under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the Convention Against Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT).

Australia has traditionally accepted that there are a number of rights that are important and should be acknowledged. The ‘right to life’ was acknowledged by Australia when it voted for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the General Assembly of the United Nations on 10 December 1948. It is also a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966, with entry into force on 23 March 1976. Article 6 clause 1 of the Covenant states: ‘Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life’. The death penalty is no longer imposed in Australia, but the option remains for it to be reintroduced, and the common law tradition has not viewed the imposition of the death penalty, subject to the individual receiving a trial, as a fundamental breach of the right to life. The killing of people is still, however, used by the Australian government when it engages in aggressive foreign interventions.

Australia acknowledged its long-standing acceptance that the right to ‘liberty’ is a fundamental, if derogable, right when it became a party to Article 3 of the Declaration of Human Rights, and also Article 9 that states, ‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile’. Australia also accepted the importance of the right to liberty when it became a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopting Article 9 of the Covenant which states:

Article 9

- Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. No one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.

- Anyone who is arrested shall be informed, at the time of arrest, of the reasons for his arrest and shall be promptly informed of any charges against him.

- Anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge shall be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorized by law to exercise judicial power and shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release. It shall not be the general rule that persons awaiting trial shall be detained in custody, but release may be subject to guarantees to appear for trial, at any other stage of the judicial proceedings, and, should occasion arise, for execution of the judgement.

- Anyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings before a court, in order that that court may decide without delay on the lawfulness of his detention and order his release if the detention is not lawful.

- Anyone who has been the victim of unlawful arrest or detention shall have an enforceable right to compensation.

Article 9 of the Covenant basically adopts the common law position traditionally followed in the criminal law jurisdictions in Australia. The Covenant links arrest with the trial proper, thus highlighting the importance of pre-trial procedures that are essential for ensuring a fair trial.

The right that ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel or degrading treatment or punishment’ is contained in Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is also a right accepted in Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which states: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. In particular, no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation’. The right is also incorporated in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. It is a non derogable right even during times of national emergency. There are a number of instances where this right has been accepted in Australian statute law,[1] and it is part of the common law tradition. The right is fragile and where abuses occur or where other rights are abrogated it cannot be guaranteed.

The right to a fair trial can be found in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it states: ‘Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him’, and Article 11 which states:

- Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

- No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

The ICCPR also stresses the importance of a fair trial and in Article 14 it provides for a number of elements necessary for a fair trial:

- All persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law. The Press and the public may be excluded from all or part of a trial for reasons of morals, public order (ordre public) or national security in a democratic society, or when the interest of the private lives of the parties so requires, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice; but any judgement rendered in a criminal case or in a suit at law shall be made public except where the interest of juvenile persons otherwise requires or the proceedings concern matrimonial disputes or the guardianship of children.

- Everyone charged with a criminal offence shall have the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law.

- In the determination of any criminal charge against him, everyone shall be entitled to the following minimum guarantees, in full equality:

- To be informed promptly and in detail in a language which he understands of the nature and cause of the charge against him;

- To have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his defence and to communicate with counsel of his own choosing;

- To be tried without undue delay;

- To be tried in his presence, and to defend himself in person or through legal assistance of his own choosing; to be informed, if he does not have legal assistance, of this right; and to have legal assistance assigned to him, in any case where the interests of justice so require, and without payment by him in any such case if he does not have sufficient means to pay for it;

- To examine, or have examined, the witnesses against him and to obtain the attendance and examination of witnesses on his behalf under the same conditions as witnesses against him;

- To have the free assistance of an interpreter if he cannot understand or speak the language used in court;

- Not to be compelled to testify against himself or to confess guilt.

- In the case of juvenile persons, the procedure shall be such as will take account of their age and the desirability of promoting their rehabilitation.

- Everyone convicted of a crime shall have the right to his conviction and sentence being reviewed by a higher tribunal according to law.

- When a person has by a final decision been convicted of a criminal offence and when subsequently his conviction has been reversed or he has been pardoned on the ground that a new or newly discovered fact shows conclusively that there has been a miscarriage of justice, the person who has suffered punishment as a result of such conviction shall be compensated according to law, unless it is proved that the non-disclosure of the unknown fact in time is wholly or partly attributable to him.

- No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again for an offence for which he has already been finally convicted or acquitted in accordance with the law and penal procedure of each country.

On 13 August 1980 Australia agreed to be bound by the ICCPR subject to reservations. Australia agreed to be bound by the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, on 25 September 1991. Australia’s joining recognised the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations and its function to receive and consider communications from people who claim violation by Australia of their covenanted rights. The findings of the Human Rights Committee are not enforceable.

The ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) was an executive act that does not incorporate it into Australian law in a way that binds, and, unless the Parliament passes legislation specifically adopting the provisions,[2] then it cannot be used to force the legislature or the courts to protect fundamental rights. Under the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) the Australian Human Rights Commission was established and is responsible for monitoring Australia’s compliance with the ICCPR. Its role is advisory.

The ratification of these treaties means that Australia has voluntarily agreed to protect the rights contained in them. However, without the rights being adopted in a Charter of Rights (such a charter does not exist in Australia) they can be derogated through legislation, thus removing their relevance or significantly limiting their application. Attempts have been made through the federal parliament to introduce a statutory Bill of Rights. The first attempt was in 1973 but opposition to it ensured it was not enacted. In 1985 a Bill passed the House of Representatives but was defeated in the Senate. In 1988 a referendum was defeated that would have extended rights to religious freedom, compensation for the acquisition of property and trial by jury. The Australian Capital Territory enacted the Human Rights Act 2004 which declares a number of rights. Victoria enacted the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 which also declares a number of rights. Neither Act binds the respective parliaments.

The difficulty in entrenching any right by way of a statutory Bill of Rights or directly in the Constitution is primarily because it meets political resistance. Attempts to include an anti-discrimination clause in the Constitution could, for example, stop the federal parliament from successfully enacting statutes such as the Northern Territory Emergency Response Act 2007 that pursuant to section 132 excluded the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 from operation whilst it was in force. Then Prime Minister Tony Abbott perhaps reflected the position taken by many past and present parliamentarians who do not want to be restricted in removing rights when they want. They also do not want courts intervening when they remove rights. Abbott is reported as stating: what ‘none of us really want to see is the ordinary legislation of Government, the ordinary operation of the executive and legislative power too readily subject to second-guessing by non-elected judges, and that’s the difficulty with trying to entrench that kind of a clause in the constitution’.[3] Abbott’s reference to ‘non-elected judges’ who ‘second-guess’ the ‘ordinary legislative agenda’, is designed to assert the paramount position of the executive over the judiciary.

Separation of Powers

Chapter III of the Constitution provides for the judicial power of the Commonwealth to be vested in the High Court. Section 80 provides for trial by jury for any indictable offence against the law of the Commonwealth. It is one of the few rights clearly stated in the Constitution that cannot be removed by Parliament. However, it is a right that is receding at State level where trial by judge alone is allowed.

Section 71, which vests judicial power in the High Court, has been consistently interpreted by the Court as requiring judges to decide cases independently of the executive government. French CJ., in South Australia v Totani, highlights the prevailing view of the judiciary, as expressed in decided cases, that the courts are independent of executive government when he states:

Courts and judges decide cases independently of the executive government. That is part of Australia’s common law heritage, which is antecedent to the Constitution and supplies principles for its interpretation and operation. Judicial independence is an assumption which underlies Ch III of the Constitution, concerning the exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth. It is an assumption which long predates Federation.[4]

French CJ found this way in 2010, but there had been no doubt, at least in the minds of the majority of the justices of the High Court, that it has an independent role from the executive and that it determined contentious issues regarding fundamental rights including life and liberty. Griffith CJ., over a hundred years before French CJ., made the point in Huddart, Parker & Co Pty Ltd v Moorehead, stating about judicial power:

I am of opinion that the words “judicial power” as used in sec. 71 of the Constitution mean the power which every sovereign authority must of necessity have to decide controversies between its subjects, or between itself and its subjects, whether the rights relate to life, liberty or property. The exercise of this power does not begin until some tribunal which has power to give a binding and authoritative decision (whether subject to appeal or not) is called upon to take action.[5]

The approach adopted by the High Court is that statute law is to be interpreted consistently with the common law. This has been a long held position and can be first found in Potter v Minahan when O’Connor J in 1908 referred with approval to Maxwell on The Interpretation of Statutes.[6] He stated:

It is in the last degree improbable that the legislature would overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law, without expressing its intention with irresistible clearness 32 Cranch., 390.; and to give any such effect to general words, simply because they have that meaning in their widest, or usual, or natural sense, would be to give them a meaning in which they were not really used.[7]

The requirement was that taking away of a common law right required the legislature to show it intended the consequence by ‘express words or necessary implication’.[8] In this case it was decided that every British subject born in Australia, whose home was Australia, had a right to enter and leave Australia. Such a limit on executive or parliamentary power goes no further than requiring the Parliament to use express words if it wants to remove a right. The only way this could be stopped is if the Constitution was interpreted in a way that showed the right was protected by it.

Chapter III provides a framework for the High Court as the judicial arm of government. However, attached to judicial power, by way of judicial interpretation, there have developed a number of fundamental legal rights and due process rights. These rights and processes, which are designed to allow access through the courts to a substantive right, have grown very slowly over hundreds of years and have occasionally been incorporated in statutes. In the High Court case of Re Tracey; Ex parte Ryan, Deane J found that section 71 was the only guarantee of due process rights, stating, to ‘ignore the significance of the doctrine or to discount the importance of safeguarding the true independence of the Judicature upon which the doctrine is predicated is to run the risk of undermining, or even subverting, the Constitution’s only general guarantee of due process’.[9] The procedural rights that are part of the process which the courts find necessary for their functioning have been regarded as an area upon which the Parliament cannot trespass. The process involves natural justice and is founded on the separation of powers. Mason C.J., Dawson and McHugh JJ., in Leeth v Commonwealth, make the point ‘that any attempt on the part of the legislature to cause a court to act in a manner contrary to natural justice would impose a non-judicial requirement inconsistent with the exercise of judicial power . . . .’[10]

The Communist Party Case,[11] is an example of where the High Court found that an Act dissolving the Communist Party and allowing the Governor-General to declare specified people disqualified from holding office in trade unions was an attempt to take over judicial power.

In the High Court case of Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration Local Government & Ethnic Affairs, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ., found that the Constitution did not allow the executive government to make laws which were inconsistent with the essential character of a court or that was of a nature of judicial power.[12]

The question of what is judicial power was answered by Jacob J in the High Court case of R v Quinn; Ex parte Consolidated Food Corporation, where he found the judicial power concerned basic rights that were inherited and protected by an independent judiciary. He stated:

[T]he rights referred . . . to are the basic rights which traditionally, and therefore historically, are judged by that independent judiciary which is the bulwark of freedom. The governance of a trial for the determination of criminal guilt is the classic example. But there are a multitude of such instances. [13]

Ultimately the purpose of the rights and processes are linked to protecting the right to liberty and to ensuring that individuals receive a fair trial.

The separation of powers is said to advance two constitutional objectives, these being, judicial independence and liberty. In Wilson v Minister for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs (“Hindmarsh Island Bridge case”) Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey, McHugh and Gummow JJ., stress the nexus between the separation of powers, judicial independence and liberty, stating: ‘The separation of the judicial function from the other functions of government advances two constitutional objectives: the guarantee of liberty and, to that end, the independence of Ch III judges’.[14]

The independence and impartiality of the judicial arm of government has been stressed in a number of cases, and without it the court is not exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth. In North Australian Legal Aid v Bradley, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ refer to previous cases and stress the need for impartiality if public confidence in the judicial system is to be maintained.[15] However, the boundaries of the power of the judiciary[16] seem to be limited mainly to conducting a fair trial. The only power the High Court seems to acknowledge that it possesses to ensure a fair trial is the power to stay the trial. This limitation allows the Parliament to introduce laws that remove the right to liberty and to dispense with all those rights which are the framework that allows basic rights to be protected by the courts. The only requirement, if pre-existing rights are removed, is that the removal does not affect a fair trial, or where it does that the judiciary is not involved in the process. Even this requirement is not absolute where national security legislation limits procedural rights such as disclosure.

Australian judges are far from isolated in their view that judges should be impartial and independent. The Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary (‘Basic Principles’ and the Bangalore Principles on Judicial Conduct (‘Bangalore Principles’) were endorsed by the United Nations.[17] The Basic Principles, Articles 1 to 7 states:

Independence of the Judiciary

- The independence of the judiciary shall be guaranteed by the State and enshrined in the Constitution or the law of the country. It is the duty of all governmental and other institutions to respect and observe the independence of the judiciary.

- The judiciary shall decide matters before them impartially, on the basis of facts and in accordance with the law, without any restrictions, improper influences, inducements, pressures, threats or interferences, direct or indirect, from any quarter or for any reason.

- The judiciary shall have jurisdiction over all issues of a judicial nature and shall have exclusive authority to decide whether an issue submitted for its decision is within its competence as defined by law.

- There shall not be any inappropriate or unwarranted interference with the judicial process, nor shall judicial decisions by the courts be subject to revision. This principle is without prejudice to judicial review or to mitigation or commutation by competent authorities of sentences imposed by the judiciary, in accordance with the law.

- Everyone shall have the right to be tried by ordinary courts or tribunals using established legal procedures. Tribunals that do not use the duly established procedures of the legal process shall not be created to displace the jurisdiction belonging to the ordinary courts or judicial tribunals.

- The principle of the independence of the judiciary entitles and requires the judiciary to ensure that judicial proceedings are conducted fairly and that the rights of the parties are respected.

- It is the duty of each Member State to provide adequate resources to enable the judiciary to properly perform its functions.

The Bangalore Principles refer to a series of values. In terms of independence the principle called Value 1 states: ‘Judicial independence is a pre-requisite to the rule of law and a fundamental guarantee of a fair trial. A judge shall therefore uphold and exemplify judicial independence in both its individual and institutional aspects’. In respect of impartiality the principle called Value 2 states: ‘Impartiality is essential to the proper discharge of the judicial office. It applies not only to the decision itself but also to the process by which the decision is made’.

The Interconnection Between Fundamental Legal Rights

The overarching right to which all other fundamental legal rights are linked is the right to liberty. The right to silence, the presumption of innocence, and the right to legal representation provide some of the procedural rights that assist with preserving personal liberty. The tension between individual liberty and the desire of governments to control citizens manifests itself in laws restricting individuals and groups. The right to liberty applies most obviously in the criminal justice system where freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention is an example of the right.

Liberty

The right to liberty is a concept that has gradually developed in the common law world. It has grown to become a foundation of the common law: from the Magna Carta 1215, Habeas Corpus Act 1679, the Petition of Right 1628, the Bill of Rights 1689 and the Act of Settlement 1701. It has been accepted as the most important of common law rights by Australian courts. In the High Court of Australia in the case of Williams v The Queen, Mason and Brennan JJ endorsed the propositions that personal liberty was the most important of all common law rights, and that its arbitrary removal would soon lead to the end of all other rights. They stated:

The right to personal liberty is, as Fullagar J. described it, “the most elementary and important of all common law rights” (Trobridge v Hardy [1955] HCA 68; (1955) 94 CLR 147, at p 152). Personal liberty was held by Blackstone to be an absolute right vested in the individual by the immutable laws of nature and had never been abridged by the laws of England “without sufficient cause” (Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford 1765), Bk.1, pp.120-121, 130-131). He warned:

” Of great importance to the public is the preservation of this personal liberty: for if once it were left in the power of any, the highest, magistrate to imprison arbitrarily whomever he or his officers thought proper … there would soon be an end of all other rights and immunities.”

That warning has been recently echoed. In Cleland v The Queen [1982] HCA 67; (1982) 151 CLR 1, at p 26, Deane J. said:

” It is of critical importance to the existence and protection of personal liberty under the law that the restraints which the law imposes on police powers of arrest and detention be scrupulously observed.”

The right to personal liberty cannot be impaired or taken away without lawful authority and then only to the extent and for the time which the law prescribes.[18]

The fundamental importance of the right to personal liberty has not been disapproved of in any subsequent High Court case. However, it has been abridged by the Parliament by laws designed to focus on crimes committed for ideological, religious or political reasons.

The High Court of Australia is far from alone when it stresses the importance of liberty. Apart from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights, the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, also recognises the importance of liberty:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Many European countries have also recognised the importance of liberty. Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights provides that everyone has the right to liberty and security of person, and that any arrest, conviction and detention has to be lawful.

The historical development of ‘liberty’ as a concept within the legal systems of the common law world is but one small part its story. The 18th Century concluded with the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a Bill of Rights in the United States, anti-slavery campaigns and revolutions against arbitrary government. The fight had gone on from earlier times when people struggled for liberty of conscience and liberty in politics. Once restricted by the Divine Right of Kings and later by dictators and executive governments, liberty has been at the core of an ongoing fight against absolutism.[19] If legal protections are removed then the form of government will matter little because the right to liberty will be at the whim of the ruling group.

As recently as 1992, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ., in Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration Local Government & Ethnic Affairs, held that the involuntary detention of a citizen, except in a limited number of exceptional cases, was a Chapter III function and therefore the exclusive role of the courts. They found that the Chapter III function of ‘adjudgment and punishment of criminal guilt’ was a matter of ‘substance not mere form’, and that ‘the involuntary detention of a citizen in custody by the State is penal or punitive in character and, under our system of government, exists only as an incident of the exclusively judicial function of adjudging and punishing criminal guilt’.[20] This was the case except in exceptional circumstances that involved: awaiting trial and this to be under the supervision of the courts; in cases of mental illness or infectious disease; the traditional powers of Parliament to punish for contempt; and punishment for breaches of military discipline.[21] The court found that aliens could be detained for the purposes of deportation and to allow for determination of admission to the country.

The High Court in 1997 added to the number of exceptions to court supervised detention listed in Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration Local Government & Ethnic Affairs when it included Aboriginal children taken from their families. The Court concluded that the number of exceptions to court supervised detention is not closed. In Kruger v Commonwealth (“Stolen Generations case”) Toohey, Gaudron and Gummow JJ., rejected the argument by the plaintiff that the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families without court order was ‘punitive’. Gummow J. said: ‘The powers of the Chief Protector to take persons into custody and care under the 1918 Ordinance were, whilst that law was in force, and are now, reasonably capable of being seen as necessary for a legitimate non-punitive purpose (namely the welfare and protection of those persons) rather than the attainment of any punitive objective’.[22]

Gaudron J went further and found that judicial supervision of involuntary detention was not a part of the powers given to the courts under Chapter III of the Constitution. She stated:

[I]t cannot be said that the power to authorise detention in custody is exclusively judicial except for clear exceptions. I say clear exceptions because it is difficult to assert exclusivity except within a defined area and, if the area is to be defined by reference to exceptions, the exceptions should be clear or should fall within precise and confined categories. ….

Once exceptions are expressed in terms involving the welfare of the individual or that of the community, it is not possible to say that they are clear or fall within precise and confined categories. More to the point, it is not possible to say that, subject to clear exceptions, the power to authorise detention in custody is necessarily and exclusively judicial power. Accordingly, I adhere to the view that I tentatively expressed in Lim, namely, that a law authorising detention in custody is not, of itself, offensive to Ch III. (emphasis added)

This approach accepts a restriction on liberty where it is claimed not to be punitive because aliens and welfare issues are involved. The reasoning is a shift away from the principle of liberty as an absolute right as clearly stated in R v Williams[23], although not a denial of its importance. Because the categories of unsupervised court detention are not closed, it remains to be seen how far the High Court will go to allow for it.

In 2004 the majority of the High Court in Al-Kateb v Godwin[24] followed Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration Local Government & Ethnic Affairs. It found in Al-Kateb’s case that, because he was an alien, in his case a stateless person, he could be held indefinitely because the detention was administrative not punitive. Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ, in the minority, found that, because the purpose of section 196 of the Immigration Act 1958 could not be carried out, he should be released.

Gleeson CJ found that the Migration Act 1958 provided for the administrative detention of un-lawful non-citizens, and that ‘unlawful non-citizens are aliens who have entered Australia without permission, or whose permission to remain in Australia has come to an end. In this context, alien includes a stateless person, such as the appellant. Detention is mandatory, not discretionary’.[25] However, whilst not excluding indefinite mandatory detention, he construed the Act in a way that did not allow for it.[26]

Whether involuntary detention requires judicial supervision is now a moot point especially in the light of anti-terrorism legislative changes in the 21st Century. The treaties that Australia has signed are not enforceable in Australia and no Bill of Rights exists that would allow the courts to restrict the arbitrary use of power by Parliament.

The one area where there appears to be no doubt of the powers conferred by Chapter III of the Constitution on the courts is the right to ensure a fair trial, which is also one of the non-derogable rights contained in the ICCPR. As part of enabling a fair trial there are a number of procedural rights that are accepted as necessary if there is to be a fair trial. Those procedural rights to varying degrees have been attached to Chapter III of the Constitution. They include: the right to legal representation in certain circumstances; the right to silence; the presumption of innocence; the right against self-incrimination; that the burden of proof in criminal trials rests with the prosecution; that the standard of proof in criminal trials is beyond reasonable doubt; and that an accused has the right to the disclosure of evidence both in favour of the prosecution and in favour of the defence in criminal cases. Some of these rights could fall into the category of quasi-substantive rights.[27]

Right to Legal Representation

An important right that has become recognised as a due process right protected by Chapter III of the Constitution, through the implied right to a fair trial, is the right to legal representation in certain circumstances. In Dietrich v R, Mason CJ, and McHugh J., with whom a majority of the court agreed, found that at common law an accused person did not have a right to the provision of a lawyer at public expense. However, they recognised that courts had power to a stay proceeding where the proceeding would result in an unfair trial and that in most cases where a person was charged with a serious offence the representation of an accused was essential to a fair trial.[28]

They referred to previous cases that found the right to a fair trial ‘according to law [is] a fundamental element of our criminal justice system ((1) Jago v. District Court (N.S.W.) [1989] HCA 46; (1989) 168 CLR 23, per Mason C.J. at p 29; Deane J. at p 56; Toohey J. at p 72; Gaudron J. at p 75.)’, and that ‘the inherent jurisdiction of courts extends to a power to stay proceedings in order “to prevent an abuse of process or the prosecution of a criminal proceeding … which will result in a trial which is unfair” ((4) Barton v. The Queen [1980] HCA 48; (1980) 147 CLR 75, at pp 95-96; Williams v. Spautz [1992] HCA 34; (1992) 66 ALJR 585; 107 ALR 635.)’. [29] They proceeded to note that there ‘has been no judicial attempt to list exhaustively the attributes of a fair trial. . . because, in the ordinary course of the criminal appellate process, an appellate court is generally called upon to determine, as here, whether something that was done or said in the course of the trial, or less usually before trial ((5) Reg. v. Glennon [1992] HCA 16; (1992) 173 CLR 592.), resulted in the accused being deprived of a fair trial and led to a miscarriage of justice’.[30]

In order to provide support for their proposition that there are due process rights that should be found in Australian law, Mason and McHugh JJ referred to the ‘various international instruments and express declarations of rights in other countries have attempted to define, albeit broadly, some of the attributes of a fair trial. Article 6 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (“the ECHR”) enshrines such basic minimum rights of an accused as the right to have adequate time and facilities for the preparation of his or her defence ((6) Art.6(3)(b).) and the right to the free assistance of an interpreter when required ((7) Art.6(3)(e)). Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“the ICCPR”), to which instrument Australia is a party ((8) Australia signed the ICCPR on 18 December 1972 and ratified it on 13 August 1980), contains similar minimum rights, as does s.11 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms ((9) Pt 1 of the Constitution Act 1982, enacted by the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.)). Similar rights have been discerned in the “due process” clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution’.[31]

Mason and McHugh JJ referred to the history of legal representation and noted: ‘It is little more than one hundred and fifty years since legislation was enacted to provide that all accused persons be permitted to be represented by counsel. Prior to the passage of The Trials for Felony Act 1836 . . . the common law of England did not recognize the right of a person charged with a felony to be defended by counsel. This prohibition . . . appears to date back beyond the limits of legal memory. . . .’[32]

Whilst the right to legal representation may now be part of the common law, enshrined in certain circumstances, as part of the fair trial process in the Constitution, the right is limited and its application to representation prior to a trial commencing can be limited or non-existent. The acceptance by the High Court of the right to legal representation acknowledges the worth of such representation to an accused person. It also in effect acknowledges the dependent interrelationship between the judiciary and legal representatives. Those who represent accused people have a duty to robustly defend them, and they are also officers of the court bound by a number of ethical obligations including the requirement that they not mislead the court.

The High Court has introduced a limited right that only applies to one stage of the trial process in serious criminal matters. Whilst it can be regarded as a positive protection, the effectiveness of a legal representative is contingent upon there being substantive and procedural laws that protect fundamental legal rights. Otherwise the lawyer is simply advising a person confronting the law that he or she has very few rights and can be kept under arrest, interrogated and must answer the questions. Where some of the provisions contained in anti-terrorism legislation apply, a defence lawyer would also be required to advise a client that if they did not answer the questions of the interrogators that they could be charged with an offence that carried a significant custodial penalty.

Right to Silence

The origin of the right to silence, viewed from the modern perspective, can be seen to have developed from the laws relating to the admissibility of confessions in criminal trials and related legal rights that have developed over the centuries. The laws related to admissions are intertwined with a number of fundamental legal rights including: the right to silence; the presumption of innocence; the right against self-incrimination; and the guarantee against inhuman and degrading treatment.

Torture developed as part of the fact gathering process in the jurisdictions applying Roman-canon law. Common methods of torture included the rack and the thumbscrew. In England trial by ordeal was gradually replaced by trial by jury. The English courts did not initially require an accused to submit to trial by jury. The passing of the Statute of Westminster 1275 allowed those charged with capital offences who did not plead to be subject to ‘peine forte et dure’. This involved placing progressively heavier stones on the chest of the accused until a plea was entered or death resulted. Peine forte et dure was not abolished by statute until 1772.

In Rees v Kratzmann, Windeyer J noted the common law traditional objection to compulsory examination and forced self-incrimination and linked it to a hatred of the Star Chamber and ‘the cherished view of English lawyers that their methods are more just than are the inquisitional procedures of other countries’.[33]

The gradual elimination of torture as an acceptable means of gathering evidence is described in leading United States case of Miranda v Arizona.[34] Chief Justice Warren, delivering the opinion of the Court, stated:

Over 70 years ago, our predecessors on this Court eloquently stated:

‘The maxim nemo tenetur seipsum accusare had its origin in a protest against the inquisitorial and manifestly unjust methods of interrogating accused persons, which [have] long obtained in the continental system, and, until the expulsion of the Stuarts from the British throne in 1688, and the erection of additional barriers for the protection of the people against the exercise of arbitrary power, [were] not uncommon even in England. While the admissions or confessions of the prisoner, when voluntarily and freely made, have always ranked high in the scale of incriminating evidence, if an accused person be asked to explain his apparent connection with a crime under investigation, the ease with which the [384 U.S. 436, 443] questions put to him may assume an inquisitorial character, the temptation to press the witness unduly, to browbeat him if he be timid or reluctant, to push him into a corner, and to entrap him into fatal contradictions, which is so painfully evident in many of the earlier state trials, notably in those of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, and Udal, the Puritan minister, made the system so odious as to give rise to a demand for its total abolition. The change in the English criminal procedure in that particular seems to be founded upon no statute and no judicial opinion, but upon a general and silent acquiescence of the courts in a popular demand. But, however adopted, it has become firmly embedded in English, as well as in American jurisprudence. So deeply did the iniquities of the ancient system impress themselves upon the minds of the American colonists that the States, with one accord, made a denial of the right to question an accused person a part of their fundamental law, so that a maxim, which in England was a mere rule of evidence, became clothed in this country with the impregnability of a constitutional enactment.’ Brown v. Walker, 161 U.S. 591, 596 -597 (1896).

Over centuries it has become established that the right to silence is a necessary part of the criminal justice system designed to limit the power of the state to extract confessions. It is also understood to be linked to the privilege against self-incrimination. The development of the right to silence is not adequately described in the cases; there was a merging of the concept of beyond reasonable doubt, Christian theology, the development of jury trials and how facts and guilt were found.[35] Indeed, it was not until 1898 that prisoners were allowed to give sworn testimony, and substantive acceptance of cross examination was allowed, and representation of an accused took all of the 19th Century to develop.[36]

Torture to obtain confessions was commonplace in the early part of 19th Century in New South Wales. Woods notes, ‘The fact that torture to obtain confessions was illegal seems not to have been obvious to the magistrates of New South Wales before 1825 or else the fact had been simply ignored’.[37] The Evidence Law Act 1858 should have assisted the magistrates in overcoming their ignorance. Section 11 of the Act stated:

No confession which is tendered in evidence on any criminal proceedings shall be received which has been induced by any untrue representation or by any threat or promise whatever and every confession made after any such representation or threat or promise shall be deemed to have been induced thereby unless the contrary be shewn.[38]

If there was any doubt about the right to silence in Australia it should have been settled when the majority in the High Court of Australia in Petty & Maiden v R stated:

A person who believes on reasonable grounds that he or she is suspected of having been a party to an offence is entitled to remain silent when questioned or asked to supply information by any person in authority about the occurrence of an offence, the identity of the participants and the roles which they played. That is a fundamental rule of the common law which, subject to some specific statutory modifications, is applied in the administration of the criminal law in this country. An incident of that right of silence is that no adverse inference can be drawn against an accused person by reason of his or her failure to answer such questions or to provide such information. To draw such an adverse inference would be to erode the right of silence or to render it valueless.[39]

Section 89 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) substantially reflected the common law position outlined by the High Court in Petty’s case. This has now been amended and the amendments allow for an adverse inference to be drawn in certain circumstances. The obvious consequence of weakening the right to silence, as has happened with the anti-terrorism legislation of the 21st Century, is that it effectively allows agents of the state to threaten an accused if silence is maintained. Whilst this type of threat is limited and does not allow for torture, it does involve a reactionary process that is more in tune with times when torture was common. In the English case of Lam Chi-Ming v The Queen, the idea that a person could be compelled to engage in self-incrimination was regarded as behaviour that did not belong in a civilised society. It was found that wrongful acts by the police can render a confession involuntary and inadmissible.[40]

The number of Australian cases supporting the right to silence is numerous;[41] the number of instances where parliaments have removed or limited the right is growing. As found by Gibbs CJ in Sorby v Commonwealth, the fundamental common law right against self-incrimination was not protected by the Constitution ‘and like other rights and privileges of equal importance it may be taken away by legislative action’.[42]

The use of torture and other physical and psychologically violent coercive techniques to gather confessions has been modified since the days when ‘peine forte et dure’ was the norm, but techniques involving the use of force have not ceased and vigilance is required to stop such coercive practices from flourishing. There are many examples supporting the proposition that the police should not be relied upon to ensure that pre-trial procedures do not involve coercion, especially if a fundamental legal right is removed. The Final Report of Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service contained the following observation: ‘In the course of the Royal Commission, evidence has been received from a number of police acknowledging their involvement in assaults and in various forms of larceny. The concern generated by the evidence, is that only the tip of an iceberg has been revealed’.[43] The removal of the right to silence at the pre-trial stage reduces one of the fetters on investigative police, thus making it easier for abuses to occur. The removal of the right, however, also has consequences during a trial; it introduces the requirement for judges and juries to draw an adverse inference if a person remains silent. There is abundant evidence to support the proposition that judges will comply with the requirement to drawn an adverse inference where the law demands it. They have no distinguishing qualities that make them immune from unfair prejudicial reasoning.

Moreover, the criminal justice system is fragile when it comes to its ability to ensure a fair trial. The examples of the fragility are many, ranging from failed investigations that have led to wrongful arrests and detentions,[44] to a combination of failed investigations and trials that were later found to be flawed.[45] Wrongful convictions are not the sole prerogative of the Australian criminal justice system. The United Kingdom in recent times has had a number of high profile cases that resulted in wrongful convictions.[46] In the United States the number of cases where people have been wrongfully convicted is too numerous to warrant listing.[47] The extra pressure that is applied by the removal or restriction of fundamental legal rights places additional pressure on a system that can fail to provide a fair trial.

The anti-terrorism legislation of the 21st Century enacted by the Australian Parliament in its questioning and detention procedures excludes the right to silence and requires those subject to it to answer or be criminally charged. In summary the right to silence became part of the laws controlling procedure and the admissibility of evidence. Its existence at the pre-trial stage assists in ensuring the integrity of the justice system. It also aids in promoting the reliability of evidence brought before the courts. A person forced to answer on penalty of imprisonment or under some other form of duress, may well call a stop to the harassment by giving an answer regardless of its accuracy or truth. This would equally apply to a person who might be able to provide relevant evidence as to one who could not.

Presumption of Innocence

The presumption of innocence is often promoted by politicians, especially when they are asked to comment on the alleged criminal behaviour of one of their colleagues.[48] The presumption of innocence stays with an accused until such time as a tribunal of fact finds the accused guilty; this is said to have the effect of maintaining the burden of proof with the prosecution throughout the trial. The presumption is found in the English common law and has grown to be accepted as a necessary part of pre-trial and trial procedure. In Woolmington v DPP, Viscount Sankey LC states:

If at any period of a trial it was permissible for the judge to rule that the prosecution had established its case and that the onus was shifted on the prisoner to prove that he was not guilty and that unless he discharged that onus the prosecution was entitled to succeed, it would be enabling the judge in such a case to say that the jury must in law find the prisoner guilty and so make the judge decide the case and not the jury, which is not the common law.[49]

In Tumahole Bereng v R the court explained the link between the presumption of innocence and the right to silence. It stated: ‘To hold otherwise would be to undermine the presumption of innocence in a manner as repugnant to the Proclamation of 1938 as to the common law of England’.[50] In R v Manunta the presumption stressed as a ‘basis principle of law’.[51] In Momcilovic v The Queen,[52] French CJ stressed the importance of the common law presumption of innocence, and described it as ‘an important incident of the liberty of the subject’.[53]

The standard direction given to a jury is, ‘a person charged with a criminal offence is presumed to be innocent unless and until the Crown persuades a jury that the person is guilty beyond reasonable doubt’.[54] The presumption of innocence cannot reasonably be said to apply where the right to silence is limited, because the onus of proof is shifted, at least to some degree, to a defendant. The erosion of the presumption of innocence occurs as less emphasis is placed on the requirement that the prosecution prove its case beyond reasonable doubt. Where there is a derogation of one of the fundamental legal rights, be it the right to silence, the privilege against self-incrimination, or the presumption of innocence, each one of them is necessarily damaged and as a consequence the right to liberty as protected by the requirement for a fair trial is undermined. Bound to the presumption of innocence is the requirement that the prosecution prove its case beyond reasonable doubt, this places the onus of proof on the prosecution.

An analysis of the cases suggests that so far the High Court has refused to give away the power it says it possesses under Chapter III of the Constitution to ensure a fair trial, and its one method to ensure that right: that being by way of staying cases. However, the Parliament may be able to legislate to remove the need for a criminal trial. The High Court acknowledges this power when it decided that there is no equality before the law. McHugh J makes this point very clear when he states: ‘The cumulative effect of the judgments of Dawson, Gaudron and Gummow JJ and myself in Kruger appears to mean that the “doctrine of legal equality” suggested by Deane and Toohey JJ in Leeth has been decisively rejected’.[55]

The one case that may give the parliamentarians some pause for thought before they dispense with the need for trial at all is the case of Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW),[56] where the New South Wales Parliament enacted the Community Protection Act 1994 that empowered the Supreme Court to make preventative detention orders. The Act applied to Gregory Kable who was in gaol for the manslaughter of his wife.[57] Whilst in gaol he wrote threatening letters to his children and his wife’s sister. In this case the High Court held that the State could not legislate in a way that would violate the principles underlying Chapter III. In Kable’s case the Act undermined the public confidence in the impartial administration of justice by the Supreme Court. McHugh J said, ‘ordinary reasonable members of the public might reasonably have seen the Act as making the Supreme Court a party to and responsible for implementing the political decision of the executive government that the appellant should be imprisoned without the benefit of the ordinary processes of law. Any person who reached that conclusion could justifiably draw the inference that the Supreme Court was an instrument of executive government policy’.[58]

Toohey J held the Community Protection Act 1994 incompatible with Chapter III of the Constitution.[59] Gaudron J also held that the Act was incompatible with the Constitution.[60] Gummow J held in a similar way, making the comment that the judiciary would just be seen as an arm of the executive.[61]

Disclosure

It has long been considered a fundamental right that a person not be convicted of a crime until he or she has received a fair trial according to law.[62] One of the essential components of a fair trial is that the individual know what the allegation is and receive from the prosecution the evidence it says shows the elements of the offence alleged and also such other evidence that may show the accused did not commit the offence.[63]

In Grey v The Queen, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Callinan JJ note the importance of disclosure and link it to what could have been made of the material if it had been supplied to the defence during cross-examination. They stated:

It is not difficult to imagine a fertile area of cross-examination that could have been tilled by the appellant on the basis of this false statement to whose makers Mr Reynolds was patently beholden. The letter should have been provided to the appellant, as is correctly conceded in this Court by the respondent. Its revelation and admission into evidence could have put a quite different complexion on the case for the appellant and the way in which it was conducted.[64]

Disclosure is a very clear example of the dependent relationship between those who apply the law and those who enforce it. If, for example, the police withhold relevant evidence from the prosecution that could point to the innocence of an accused person, the prosecution may never know and certainly the defence is even less likely to know. Similarly, if the prosecution has evidence that points to the innocence of an accused person and does not disclose it, the defence may never know. Although the defence can subpoena documents through a court process, the restrictions are not minor[65] and the law enforcement agency, if behaving corruptly, can simply deny the existence of the evidence sought, or claim public interest immunity[66] based on false propositions.

The substantive and procedural rights provide the necessary rules by which courts should operate and that parliaments should understand and incorporate into legislation or at least not abrogate by statute. However, none of the rights are safe where those vested with the duty to enforce the law or prosecute behave corruptly and lie and or otherwise deceive when preparing and presenting a case. The non-disclosure of relevant evidence is a clear example of corrupting procedural rights that perverts the administration of justice. Additionally, none of the rights are safe if governments legislate to detain people outside the traditional criminal trial process, or specifically exclude or modify a substantive right.

References

[1] For example, section 138 of the Evidence Act 1995 allows for the exclusion of evidence that has been improperly obtained and it refers to breaches of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as one of the factors the court can take into account. Section 138 states, inter alia:

138 Exclusion of improperly or illegally obtained evidence

(1) Evidence that was obtained:

(a) improperly or in contravention of an Australian law, or

(b) in consequence of an impropriety or of a contravention of an Australian law,

is not to be admitted unless the desirability of admitting the evidence outweighs the undesirability of admitting evidence that has been obtained in the way in which the evidence was obtained.

(f) whether the impropriety or contravention was contrary to or inconsistent with a right of a person recognised by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights . . . .

[2] Bradley v The Commonwealth [1973] HCA 34; (1973) 128 CLR 557, 582; Simsek v MacPhee (1982) 148 CLR 636, 641-644; Kioa v West [1985] HCA 81; (1985) 159 CLR 550, 570-571.

[3] Anna Henderson, ‘Government renews reservations about race discrimination ban in constitution ahead of Indigenous recognition summit’, Anna Henderson, ABC News, 4 July 2015,www.abc.net.au/news/2015-07-04/government-renews-reservations-about-race-discrimination-ban/6594726.

[4] [2010] HCA 39; (2010) 242 CLR 1, [1].

[5] [1909] HCA 36; (1909) 8 CLR 330.

[6] PB Maxwell, The Interpretation of Statutes, (Sweet and Maxwell 1905) 122.

[7] [1908] HCA 63; (1908) 7 CLR 277.

[8] Ibid.

[9] [1989] HCA 12, 2; (1989) 166 CLR 518.

[10] [1992] HCA 29; (1992) 174 CLR 455, 470.

[11] [1951] HCA 5, 50,51; (1951) 83 CLR 1.

[12] [1992] HCA 64; (1992) 176 CLR 1.

[13] [1977] HCA 62; (1977) 138 CLR 1, 13.

[14] [1996] HCA 18, 12; (1996) 189 CLR 1.

[15] [2004] HCA 31, 27; 218 CLR 146; 206 ALR 315; 78 ALJR 977.

[16] See Brendan Gogarty and Benedict Bartl, ‘Tying Kable Down: The Uncertainty About the Impartiality of State Courts Following Kable v DPP(NSW) and Why It Matters’, (2009) 32(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 75.

[17] Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Adopted by the Seventh United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders held at Milan from 26 August to 6 September 1985 and endorsed by General Assembly resolutions 40/32 of 29 November 1985 and 40/146 of 13 December 1985; Bangalore Principles on Judicial Conduct, endorsed by the United Nations Economic and Social Council resolutions 2006/23 and 2007/22.

[18] [1986] HCA 88; (1986) 161 CLR 278, 9.

[19] The fight against absolutism is described in A.C. Grayling, Towards the Light (Bloomsbury, 2007).

[20] [1992] HCA 64, 23; (1992) 176 CLR 1.

[21] Ibid.

[22] [1997] HCA 27; (1997) 190 CLR 1; (1997) 146 ALR 126; (1997) 71 ALJR 991.

[23] Above n 95.

[25] Ibid [1].

[26] Ibid [22].

[27] See Justice M.H. McHugh AC, High Court of Australia, ‘Does Chapter III of the Constitution protect substantive as well as procedural rights?’ Bar News, Summer 2001/2002, 35.

[28] [1992] HCA 57, 1; (1992) 177 CLR 292.

[29] Ibid 7.

[30] Ibid 8.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid 11.

[33] [1965] HCA 49; (1965)114 CLR 63, 3.

[34] 384 U.S. 436 (1966); see also Ullmann v United States [1956] 350 US 422 [100 L. Ed. 511].

[35] See James Q. Whitman, The Origins of Reasonable Doubt (Yale University Press, 2008).

[36] J H Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History (Butterworths, 1979) 416 – 418.

[37] G. D. Woods, A History of Criminal Law in New South Wales (Federation Press, 2002) 171.

[38] 22 Vict. No. 7 (1858) s 11.

[39] [1991] HCA 34, para 2; (1991) 173 CLR 95.

[40] [1991] 2 AC 212, 220.

[41] Hammond v The Commonwealth [1982] HCA 42; (1982) 152 CLR 188, 3, Brennan J.; Sorby v The Commonwealth [1983] HCA 10; (1983) 152 CLR 281, 5, Gibbs CJ.; RPS v R [2000] HCA 3; (2000) 199 CLR 620, 61- 62 per McHugh J.; Regina v Sellar and McCarthy [2012] NSWSC 934.

[42] [1983] HCA 10; (1983) 152 CLR 281, 298.

144 Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service, Final Report, Volume 1: Corruption, May 1997, para 4.254.

[44] See, for example, Report of the Royal Commission into The Arrest, Charging and Withdrawal of Charges Against Harold James Blackburn and Matters Associated Therewith, June 1990.

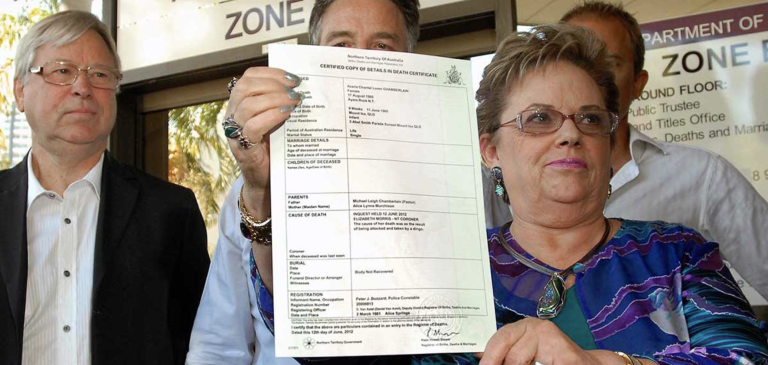

[45] Some recent examples include: Mickelberg v The Queen [2004] WASCA 145; Morgan v R [2011] NSWCCA 257, Wood v R [2012] NSWCCA 21, and Gilham v R [2012] NSWCCA 131. There is also the well-known Chamberlain case. See also Chester Porter, The Conviction of the Innocent (Random House 2007).

[46] R. v. Anne Maguire, Patrick Joseph Maguire, William John Smyth, Vincent Maguire, Patrick Joseph Paul Maguire, Patrick O’Neill and Patrick Conlon (1991) 94 Crim. App. R. 133; R v McIlkenny, Hunter, Walker, Callaghan, Hill and Power (1991) 93 Crim. App. R. 287 [The Birmingham Six].

[47] The National Registry of Exonerations lists 1,273 ‘exonerations’, A Joint Project of Michigan Law & Northwestern Law.

[48] For example, in 2013 then Trade Minister Craig Emerson defended Labor colleague Craig Thompson, who was facing a number of allegations involving corrupt practices as a trade union official. Emerson is reported as saying: ‘Let the investigative processes continue without political interference,’ he told Sky News, adding that Mr Thomson was entitled to the presumption of innocence. ‘There has been no finding of guilt against Mr Thomson.’: Kate McClymont, ‘Craig Thomson arrested by fraud squad’, Sydney Morning Herald, 31 January 2013; www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/craig-thomson-arrested-by-fraud-squad-20130131-2dmnn.html.

[49] [1935] AC 462, 480.

[50] [1949] AC 253, 270.

[51] 20 December, 1988, SC (SA) unreported.

[52] [2011] HCA 34.

[53] Ibid 44.

[54] Judicial Commission of New South Wales, Bench Book, 3-600.

[55] M.H. McHugh AC, High Court of Australia, “Does Chapter III of the Constitution protect substantive as well as procedural rights?’ Bar News, Summer 2001/2002, 41.

[56] [1996] HCA 24; (1996) 189 CLR 51.

[57] I appeared for Gregory Kable at his sentencing hearing.

[58] Ibid 40.

[59] Ibid 32.

[60] Ibid 14.

[61] Ibid 36.

[62] Jago v District Court (NSW) (1989) 168 CLR 23, 29, 56, 72; Brown [1995] 1 Cr App R 191, 198.

[63] Johnson v Miller [1937] HCA 77; (1937) 59 CLR 467.

[64] [2001] HCA 65, 18.

[65] See requirement excluding it if found to be a ‘fishing expedition’: R v Ali Tastan (1994) 75 A Crim R 498; Attorney-General (NSW) v Chidley (2008) 182 A Crim R 563. Requirement for accused to show legitimate forensic purpose: R v Taylor [2007] NSWCCA 104; R v Salem (1989) 16 NSWLR 14. Considerations if viewed as oppressive: Spencer Motors Pty Ltd v LNC Industries Ltd [1982] NSWLR 921.

[66] Alister v R [1983] HCA 45; (1984) 154 CLR 404.