The Conviction of Kathleen Folbigg

The following account is designed to provide a brief overview of the prosecution of Kathleen Folbigg and her attempts to gain her freedom.

Overview Facts

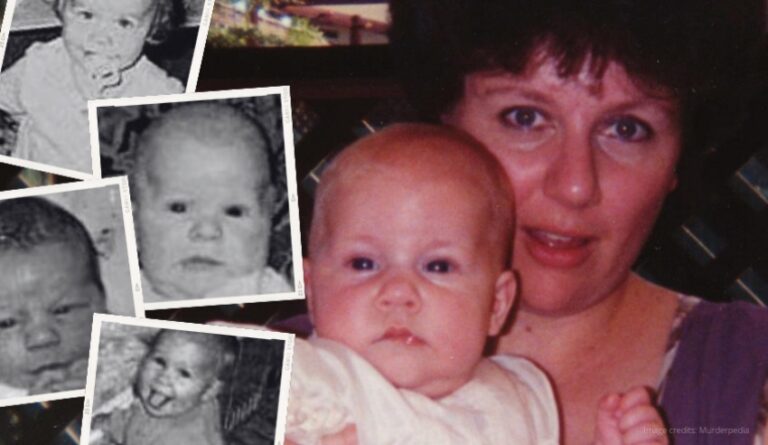

In 2003 Kathleen Folbigg stood trial on four counts of murder and one of maliciously inflicting grievous bodily harm. The counts concerned the deaths of her four children over a ten year period.

Count 1

- charged her with having murdered, on 20 February 1989, C (Caleb).

- Caleb was 19 days old at the time of his death.

Count 2

- charged her with having maliciously inflicted, on 18 October 1990, grievous bodily harm upon P (Patrick) with intent to do grievous bodily harm.

Count 3

- charged her with having murdered, on 13 February 1991, P (Patrick).

- Patrick was 8 months old.

Count 4

- charged her with having murdered, on 30 August 1993, S (Sarah).

- Sarah was 10 months old when she died.

Count 5

- charged the appellant with having murdered, on 1 March 1999, L (Laura).

- Laura was 18 months old at the time of her death.

The trial commenced on 1 April 2003 and finished on 19 May 2003 (27 days of hearings).

On 21 May 2003 the jury found her not guilty of murder of Caleb but guilty of manslaughter, guilty of maliciously inflicting grievous bodily harm on Patrick, and guilty of murder of Patrick, guilty of murder of Sarah and guilty of murder of Laura.

Ms Folbigg was sentenced on 24 October 2003 to imprisonment for 40 years with a non-parole period of 30 years. It was later reduced on appeal to a 25-year non-parole period.

Ms Folbigg appealed unsuccessfully to the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal a number of times. On the first occasion in the case cited as R v Folbigg [2003] NSWCCA 17 Ms Folbigg appealed the decision of a single judge to refuse to have her charges tried separately. The consequence of this decision allowed tendency and coincidence evidence to be used. She was the primary carer of her children, the fact that she found them unconscious was used as part of the coincidence evidence.

After the trial in an appeal seeking to overturn her convictions in Regina v Folbigg [2005] NSWCCA 23 Ms Folbigg appealed for the following reasons:

- The five charges should not have been heard together.

- The jury verdicts were unreasonable and could not be supported by the evidence.

- Prosecution experts said that they were unaware of previous cases in which three or more infants in one family died suddenly, and this was wrong.

- The judge did not properly direct the jury about coincidence and tendency evidence.

Her final appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal in Folbigg v R [2007] NSWCCA 371 Ms Folbigg asked the court to reopen the appeal on the basis that jurors had obtained the following information that: Ms Folbigg’s father killed her mother, and the length of time an infant’s body remains warm after they die. Ms Folbigg said this impacted on the jury’s decision significantly.

Ms Folbigg sought special leave to appeal to the High Court in 2005 but it was denied. One of the two judges when he refused the appeal said there was evidence of smothering with a pillow. Mr Justice Mc Hugh ACJ stated:

. . . there was no clear, natural cause of death and all the children showed signs that were consistent with smothering with a pillow. When you add the diary entries to those facts, why was it not open to the jury to conclude that the applicant had murdered the children?

There was no evidence of smothering with a pillow or anything else.

The appeal process through the courts of New South Wales ended with the attempt to have the High Court hear the case.

Meadows Law

In the first Court of Criminal Appeal case the judge considered, amongst other things, the following expert evidence[1] when deciding on the admissibility of tendency and coincidence evidence:

Dr Ophoven observed:

“It is well recognized that the SIDS [Sudden Infant Death Syndrome] process is not a hereditary problem and the statistical probability that 4 children in one sibship could die from SIDS would be infinitesimally small.” [paragraph 43]

Professor Berry’s view was as follows:

“The sudden and unexpected death of three children in the same family without evidence of a natural cause is extraordinary. I am unable to rule out that Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and possibly Laura Folbigg were suffocated by the person who found them lifeless, and I believe that it is probable that this was the case.” [paragraph 44]

Professor Herdson, when taking all 4 deaths into account, said:

“I am unaware that there have ever been three or more thoroughly investigated infant deaths in one family from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Based on all the material that I have reviewed relating to these four infant deaths, in my opinion all four infants probably died from intentional suffocation.” [paragraph 47]

Dr Susan Beal, a paediatrician, made the following statement:

“Based on the records I have examined in regards to the family Folbigg, I have no hesitation in saying I believe that all four siblings were murdered… As far as I am aware there has never been three or more deaths from SIDS in the one family anywhere in the world, although some families, later proved to have murdered their infants had infants who were originally classified as SIDS.” [paragraph 48]

The admission of such evidence introduced what is called Meadows Law which proposes that a third SIDS death is a homicide. Professor Ray Hill describes the ‘law’ and correctly identifies its sources and the fact that it was not supported by any data, case histories or references. He notes:

Whilst ‘Meadow’s Law’ is quoted frequently in the UK, I am grateful to Dr Glynn Walters for pointing out the following:

‘Professor Meadow did not originate the law. It appears to be attributable to D.J. and V.J.M. Di Maio, two American pathologists who state in their book:

It is the authors’ opinion that while a second SIDS death from a mother is improbable, it is possible and she should be given the benefit of the doubt. A third case, in our opinion, is not possible and is a case of homicide.

It is clear that the statement is the authors’ opinion. It is not a conclusion reached by analysis of their observations; no supportive data are presented and there are no illustrative case histories, or references to earlier publications. This is in striking contrast with the rest of the book which is replete with illustrative case histories and cites many references throughout. A recent examination of Meadow’s own contributions to the medical literature has likewise failed to uncover supportive pathological evidence or references to it.’[2]

There are examples of three or more infant deaths in the one family, and these examples were available at the time of the trial.[3]

It should be noted that Meadows law is generally expressed in the following ways:

- The extreme improbability that four deaths in one family can be due to natural causes.

- Four deaths in one family are so rare to be virtually impossible.

- Familial or inherited link in SIDS was/is extremely improbable.

Petition to the Governor for an Inquiry

A Petition to the Governor of New South Wales dated 26 May 2015 sought an inquiry into Ms Folbigg’s convictions. Submissions were made in support of a review of the convictions pursuant to s76 of the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001. A direction was sought that an inquiry be conducted by a judicial officer pursuant to s77(1)(a) of the Act.

The Petition included fresh evidence. Professor Cordner, Forensic Pathologist, provided a report that evaluated the evidence given by experts at trial. In the first chapter of his report he notes that the use of the word ‘asphyxia’ in questions by the prosecution and raises the issue that such questions, where they related to the cause of death, were not capable of an answer. He states: ‘Asphyxia is not a helpful word in forensic pathology, is not understood in a uniform way, is not a diagnosis, and is not diagnosable. Yet the word is at the core of the main question asked by the Prosecution: Did this child/these children suffer “an acute catastrophic asphyxiating event”? If this question was intended to be a technical question in forensic pathology, it had no content and is not capable of an answer. Ultimately, and simply, there is no forensic pathology support for the contention that any or all of these children have been killed let alone smothered.’

At trial the prosecution claim was that Ms Folbigg had smothered her children. Asphyxia was used in a way that allowed the word to be used as an equivalent to manual smothering, yet there was no evidence of smothering and the onus of proof in the trial was effectively shifted to a position where she had to prove she did not smother her children. At the same time Meadows law appeared in the way questions were answered.

Professor Cordner, concludes about the forensic pathology evidence in the case:

a) There is no forensic pathology evidence to suggest that the Folbigg children were deliberately smothered or killed.

It seems not to have been explicitly stated in the trial, but there is no forensic pathology evidence, no signs in or on the bodies, to positively suggest that the Folbigg children were smothered, or killed by any means.

- b) The lack of facial injuries is evidence against the conclusion of smothering.

The lack of external or deeper facial injuries is not a neutral factor in evaluating these deaths. In my view the lack of such injuries in all four cases is evidence against the conclusion of smothering as being the explanation for the four deaths. In none of the four Folbigg children, who all underwent autopsy, is there any bruising of the inside of the lips or frenulum or externally around the mouth or nose.

. . . .

Again, in a series of four smoothing deaths and one ALTE, [Apparent Life Threatening Event] especially where one of the deaths involved a child of 19 months (ie with teeth), the absence of any positive signs for compression of the face in all cases represents a significant finding which must be given due weight in any proper evaluation.[4]

The Inquiry

An inquiry was granted by the Governor of NSW in August 2018, and the evidence was heard from March 2019 for three weeks. The person appointed to hear the evidence was Reginald Blanch, a former Chief Justice of the District Court of New South Wales and before that Director of Public Prosecutions in New South Wales.

During the inquiry, forensic pathologists Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton were in consensus about how the children died, that is, of natural causes. Dr Allan Cala performed the autopsy on the last child Laura and concluded that her death was “undetermined” in light of the deaths of her previous siblings (evidence given at Ms Folbigg’s trial). That view changed at the Inquiry and he said that he could not exclude myocarditis as the cause of death of Laura Folbigg. Even during the trial Cala acknowledged there was no evidence of smothering in any of the children.

The Inquiry also heard evidence relating to infection and immunology, neurology, and genetics.

Professor Vinuesa and Dr Arsov (Canberra team) were engaged by Ms Folbigg’s lawyers. The team engaged by Counsel Assisting were Dr Colley, Dr Buckley and Professor Kirk (Sydney team). Both teams sequenced the genomes of the children but reached a different conclusion as to pathogenicity. There were no subject matter experts (related to CALM or cardiac genetics) called to reconcile this tension between the two groups.

Professor Schwartz (cardiac geneticist) wrote to the inquiry (after the hearings were over) to indicate the CALM2 variant is “likely pathogenic” (instead of “unknown significance” as the Sydney team concluded). The Commissioner of the inquiry declined to re-open the inquiry to hear from Professor Schwartz. The Commissioner instead dealt with this in an Addendum to his report.

The Commissioner found no reasonable doubt as to Ms Folbigg’s conviction, stating, amongst other things, “evidence which has emerged at the Inquiry, particularly her own explanations and behaviour in respect of her diaries, makes her guilt of these offences even more certain.”

Functional validation of the CALM2 variation was published by Professors Toft Overgaard, Schwartz, Vinuesa and colleagues on 17 November 2020 which concluded that the CALM2 variant was a likely and possible explanation for Sarah and Laura Folbigg’s death.

The use of Meadows Law reasoning at trial was in effect acknowledged Reginald Blanch. The Commissioner states:

‘It is accepted that it is clear from the work of the Inquiry that before 2003 there had been reported cases involving the deaths of three or more infants in the same family attributed to unidentified natural causes, or at least not established as attributable to unnatural causes. To the extent that the Crown case as left to the jury asserted or invited otherwise, that was incorrect.’[5]

He then concludes:

‘In light of the above, I am satisfied that the treatment of the issue of recurrence at trial has not resulted in a miscarriage of justice or irregularity that gives rise to a reasonable doubt as to Ms Folbigg’s guilt.’[6]

This means the following:

- At the time of the trial, there were known cases of multiple deaths in one family that were natural.

- This was not revealed to the jury. In fact, it was suggested that there were not any known cases.

- The Commissioner of 2019 inquiry acknowledged that the jury was misinformed.

- The Commissioner concluded that despite the jury being misinformed, that this did not give rise to a miscarriage of justice or even an irregularity.

To state the obvious: if a jury is told that there are no known cases where three or more children died of natural causes in one family, then they are effectively being told that they need to give more weight to the prosecution’s theory (smothering) as it is more persuasive than the proposition that the deaths were natural. The practical effect of this was to reverse the onus of proof where Ms Folbigg had to prove her innocence. They are saying that absence of evidence of smothering should indicate it that it occurred (because it cannot be excluded). To adopt this line of reasoning is circular and put the bar so unreasonably high that Ms Folbigg could never prove she didn’t kill them. This is wrong at law: the prosecution must prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. Ms Folbigg, by law, did not have to do a thing.

The Inquiry website can be found at: http://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au

Court of Appeal

In a matter that was completely separate from the Petitioning process and appeal was undertaken in the Court of Appeal in New South Wales. This appeal was unsuccessful.

Petition to the Governor for a Pardon

A Petition for a pardon was forwarded to the Governor of New South Wales on 21 March 2021. These submissions requested that the Governor exercise the pardon power pursuant to s 76 of Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW).

Sections 77 of the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW) allows the following:

- The Governor to direct that any inquiry be conducted by a judicial officer into the conviction or sentence: s77(1)(a).

- The Attorney General to refer the case to the Court of Criminal Appeal: s77(1)(b).

- The Attorney General to seek an opinion from the Court of Criminal Appeal about any point arising in the case: s77(1)(c).

- The Governor may refuse to consider the Petition: s77(3).

Note: The Governor has already referred the Petition to the Attorney General and he has said he is considering it.

- The Attorney General may refuse to consider the Petition: s77(3).

- Although the Petition asks for a pardon the Attorney General can take additional steps if he is of the opinion that it can be dealt with in other ways as well: s77(5) For example, he can refer it to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

Through acceptance of convention the Governor normally only acts on the advice of the Attorney General. The Petition does not ask for the involvement of the Attorney General of New South Wales. However, he is involved in giving advice to the Governor and can take the actions as outlined above. The Attorney General usually seeks advice from the Solicitor General and the Crown Solicitor. He can also ask any government department or agency to advise him or seek advice from anyone he wants.

The main grounds for the Pardon were:

- Ms Folbigg should be granted a pardon based on the significant positive evidence of natural causes of death for Caleb, Patrick, Sarah, and Laura. The further developments to support this are:

- Professor Schwartz (world’s leading cardiac geneticist) concluded that the CALM2 mutation found in Sarah and Laura Folbigg is ‘likely pathogenic’. Whenever a sudden death occurs without obvious causes and a ‘likely pathogenic’ mutation of this nature is found, it is scientifically appropriate to consider the mutation as the likely cause of death. This important evidence was not given the opportunity to be heard at the inquiry as the Commissioner declined to reopen the hearings to consider the evidence of Professor Schwartz.

- The likely role of the novel CALM2 mutation in Sarah and Laura’s death was confirmed in a world leading study by Professor Toft Overgaard, Professor Schwartz, Professor Vinuesa and colleagues published on 17 November 2020.[7] In this ground-breaking research the authors concluded that a fatal cardiac arrhythmia caused by the CALM2 mutation and triggered by intercurrent infections, was a reasonable explanation for Sarah and Laura’s death. This paper has been published in EP Europace (Oxford University Press), a highly respected, peer reviewed journal. This indicates that the international medical and scientific communities find the role of the CALM2 mutation in cardiac death a reasonable and likely explanation for Sarah and Laura’s deaths.

The following are the current medical explanations from the leading experts in their field for each of the Folbigg children’s deaths:

(a) Caleb died on 20 February 1989 at 19 days of age. His death was classified as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), category 2, with a finding of laryngomalacia.[8]

(b) Patrick died on 13 February 1991 at 8 months from asphyxia due to airway obstruction due to epileptic fits from an encephalopathic disorder of unknown cause (associated with blindness), as reported in his death certificate.[9]

(c) Sarah died on 30 August 1993 at 10 months of age. Her death was classified as SIDS, category 2. She died four days after seeing her general practitioner for a croupy cough and starting a course of antibiotics (flucloxacillin). Autopsy findings included a congested and haemorrhagic uvula and profuse alpha-haemolytic Streptococcus in lung cultures. Further investigation identified she carried the likely pathogenic and arrhythmogenic CALM2 mutation.[10]

(d) Laura died on 1 March 1999 at 18 months old. She died two days after being treated for a respiratory infection with paracetamol and pseudoephedrine (a medication known to trigger cardiac arrhythmias). At autopsy she was found to have florid myocarditis. Her death was initially recorded by Dr Cala as “undetermined” in light of the previous deaths of her siblings. At the inquiry, Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton indicated that they would have recorded Laura’s myocarditis as the cause of death. Dr Cala acknowledged at the inquiry that myocarditis could have been the cause of Laura’s death.[11] Further investigation identified that Laura carried the likely pathogenic CALM2 mutation.[12]

Myocarditis, medications like pseudoephedrine, and fever, are well established triggers of arrhythmia in children with a genetic susceptibility,[13] such as a likely pathogenic CALM2 mutation.[14] A summary of the conditions of each of the Folbigg children is set out on page 16 of the Supplementary Materials to the paper by Brohus et al (2020).[15]

The medical evidence that exists, especially in light of the Brohus et al (2020) functional studies, creates a strong presumption that the Folbigg children died of natural causes. A presumption that should only be displaced by overwhelming evidence to the contrary, which we submit there is not.

The Petition was endorsed before it was sent to the Governor by 90 Australian and world renowned scientists and medical practitioners. This was followed on 31 March 2021 by the endorsement of 66 Fellows of the Royal Society of New South Wales.

Dairy and Journal Entries

Some diary and journal entries created by Kathleen Folbigg were used at trial. They are currently being used as a reason to keep her in gaol. Her husband found some of them after they separated. He read them and he contacted the police. The diaries were the catalyst that led to the charging of Kathleen Folbigg. A useful although extremely limited summary of the entries and how they could be viewed is provided Sully J. in Regina v Folbigg [2005] NSWCCA 23. He states:

131 There is to be added to that material the evidence of the relevant contents of the appellant’s diary. There is a deal of this material, and it cannot be fairly compressed into a brief paraphrase. The Crown’s written submissions extract a little over five A4 pages of diary entries. I set out a number of portions of that extract, acknowledging the selectivity of that method, but concentrating on particular entries that give, in my view, a fair, representative idea of the relevant material:

“3 June 1990: This was the day that Patrick Allan David Folbigg was born. I had mixed feelings this day. whether or not I was going to cope as a mother or wether I was going to get stressed out like I did last time. I often regret Caleb & Patrick, only because your life changes so much, and maybe I’m not a Person that likes change. But we will see?

18 June 1996: I’m ready this time. And I know Ill have help & support this time. When I think Im going to loose control like last times Ill just hand baby over to someone else.

…. I have learnt my lesson this time.

4 December 1996: [found out she was pregnant]. I’m ready this time. But have already decided if I get any feelings of jealousy or anger to much I will leave Craig & baby, rather than answer being as before. Silly but will be the only way I will cope.

1 January 1997: Another year gone & what a year to come. I have a baby on the way, …… This time. I am going to call for help this time & not attempt to do everything myself any more – I know that that was the main Reason for all my stress before & stress made me do terrible things.

4 February 1997: Still can’t sleep. Seem to be thinking of Patrick & Sarah & Caleb. Makes me generally wonder whether I am stupid or doing the right thing by having this baby. My guilt of how responsible I feel for them all, haunts me, my fear of it happening again haunts me.

……. What scares me most will be when Im alone with baby. How do I overcome that? Defeat that?

16 May 1997: …. Craig says he will stress & worry but he still seems to sleep okay every night & did with Sarah. I really needed him to wake that morning & take over from me. This time Ive already decided if ever feel that way again I’m going to wake him up.

25 October 1997: …. I cherish Laura more, I miss her [Sarah] yes but am not sad that Laura is here & she isn’t. Is that a bad way to think, don’t know. I think I am more patient with Laura. I take the time to figure what is rong now instead of just snapping my cog. … Wouldn’t of handled another like Sarah. She’s saved her life by being different.

29 October 1997: felt a little angry towards Laura today. It was because I am & was very tired. … she [Laura] doesn’t push my Button any where near the extent she [Sarah] did. Luck is good for her is all I can say.

3 November 1997: Lost it with her earlier. Left her crying in our bedroom – had to walk out – that feeling was happening. And I think it was because I had to clear my head & prioritise. As I’ve done in here now. I love her I really do I don’t want anything to happen.

9 November 1997: … he [Craig] has a morbid fear about Laura. … well I know theres nothing wrong with her. Nothing out of ordinary any way. Because it was me not them. … With Sarah all I wanted was her to shut up. And one day she did.

19 November 1997: Bit nervous tonight. Laura & I are by ourselves tonight.”

“8 November [sic, December] 1997: Had a bad day today, lost it with Laura a couple of times. She cried most of the day. Why do I do that. … Got to stop placing so much importance on myself. — funny how, now she’s [Laura’s] here, we can’t seem to imagine a life without her dominating every move. Much try to release my stress somehow. I’m starting to take it out on her. Bad move. Bad things & thoughts happen when that happen. I will never happen again.”

“New Year’s Eve, 1997: Getting Laura to be next year ought to be fun. She’ll realise a Party is going on. And that will be it. Wonder if the battle of the wills will start with her & I then. We’ll actually get to see. She’s a fairly good natured baby – Thank goodness, it has saved her from the fate of her siblings. I think she was warned.”

28 January 1998: I’ve done it. I lost it with her. I yelled at her so angrily that it scared her, she hasn’t stopped crying. Got so bad I nearly purposely dropped her on the floor & left her. I restrained enough to put her on the floor & walk away. Went to my room & left her to cry. Was gone probably only 5 minutes but it seemed like a lifetime. I feel like the worst mother on this earth. Scared that she’ll leave me know. Like Sarah did. I know I was short tempered & cruel sometimes to her & she left. With a bit of help. I don’t want that to ever happen again. I actually seem to have a bond with Laura. It can’t happen again. Im ashamed of myself. I can’t tell Craig about it because he’ll worry about leaving her with me. Only seems to happen if I’m too tired her moaning, bored, wingy sound, drives me up the wall. I truly can’t wait until she’s old enough to tell me what she wants.

6 March 1998: Laura not well, really got on my nerves today, snapped & got really angry, but not nearly as bad as I used to get.

13 March 1998: Seem to have a good day. She didn’t piss me off more than a couple of times.

1 April 1998: Thought to myself today. Difference with Sarah, Pat, Caleb to Laura, with Laura I’m ready to share my life. I definitely wasn’t before.”

132 These entries make chilling reading in the light of the known history of Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and Laura. The entries were clearly admissible in the Crown case. Assuming that they were authentic, which was not disputed; and that they were serious diary reflections, which was not disputed; then the probative value of the material was, in my opinion, damning. The picture painted by the diaries was one which gave terrible credibility and persuasion to the inference, suggested by the overwhelming weight of the medical evidence, that the five incidents had been anything but extraordinary coincidences unrelated to acts done by the appellant.

His Honour’s conclusion that the diary entries were ‘damning’ is done without consideration of the context in which they were written. However, there is other equally compelling reasoning that allows for an innocent interpretation. His Honour’s conclusion that the ‘overwhelming weight of the medical evidence’ was adverse to Katherine Folbigg is overstating the strength of prosecutions medical evidence and adopting flawed reasoning as pointed out in the Professor Cordner’s Report. His Honour’s did not have available the new evidence which may have tempered his conclusion about the medical evidence.

In the appeal case Folbigg v R [2007] NSWCCA 371, McClellan CJ at CL. also stressed the use of the diary entries. He stated:

39 The Crown case relied, in part, on the contents of the appellant’s diaries. It was submitted that the diaries contained virtual admissions of guilt of the deaths of C, P and S and admissions that she realised that she was at risk of causing the death of L. The diary entries record descriptions of her state of mind from time to time, her feelings of tiredness and frustration, her feelings of guilt for having mistreated her children. Examples of relevant extracts include (emphases added):

Difficulties with caring for the children

“…And I know I’ll have help and support this time. When I think I’m going to lose control like last time I’ll just hand baby over to someone else…” (18 June 1996)

“…But I think losing my temper stage & being frustrated with everything has passed. I now just let things happen and go with the flow. An attitude I should have had with all my children if given the chance I’ll have with the next one…” (14 October 1996)

“…maybe then he will see when stress of it all is getting to be too much & save me from ever feeling like like I did before, during my dark moods. Hopefully preparing myself will mean the end of my dark moods, or at least the ability to see it coming & say to him or someone hey, help I’m getting overwhelmed here, help me out. That will be the key to his babies survival…” (6 June 1997)

“…very depressed and angry with myself, angry & upset – I’ve done it. I lost it with her. I yelled at her so angrily that it scared her, she hasn’t stopped crying. Got so bad I nearly purposely dropped her on the floor & left her. I restrained enough to put her on the floor and walk away…” (28 January 1998)

Admissions

“…I think I am more patient with [L]. I take the time to figure what is rong now instead of just snapping my cog … Wouldn’t of handled another like [S]. She’s saved her life by being different…” (25 October 1997)

“…[Craig] has a morbid fear about [L] … well I know theres nothing wrong with her. Nothing out of ordinary any way. Because it was me not them … With [S] all I wanted was her to shut up. And one day she did…” (9 November 1997)

“…She’s a fairly good natured baby – Thank goodness, it has saved her from the fate of her siblings. I think she was warned…” (31 December 1997)

“…Went to my room and left [L] to cry. Was gone probably 5 minutes but it seemed like a lifetime. I feel like the worst mother on earth. Sacred that she’ll leave me know. Like [S] did. I know I was short tempered & cruel sometimes to her & she left. With a bit of help. I don’t want that to ever happen again. I actually seem to have a bond with [L]. It can’t happen. I’m ashamed of myself. I can’t tell Craig about it because he’ll worry about leaving her with me. Only seems to happen if I’m too tired her moaning, bored, wingy sound, drives me up the wall…” (28 January 1998)

Expert evidence was not called by the defence to assist the jury with interpreting how they could consider the evidence found in the diaries.

The diaries were used by the prosecution to allow the jury to infer an admission of guilt. It was certainly open for the jury to use the diary entries in a way that was highly and unfairly prejudicial.

An alternative explanation for diary entries were that they were made by a weary and emotional person who sought to express her feelings in the written word as a cathartic process, expressing emotions that have often been reported as not uncommon amongst women experiencing childbirth and motherhood. She speaks of the feelings of alienation from her husband, of feeling fat and unattractive, of feeling alone. They can also been seen as seeking to find out why her children died. There are no confessions.

It should be noted that Kathleen Folbigg did not take her diary when she left her husband and told him to dispose of any excess things she had left. There was no attempt on her part to conceal her private writings. There are many difficulties with third parties attempting to interpret accurately private records of feelings of a person, particularly when written in highly emotional states of mind. There was a failure to take into account underlying aspects of the literal word, in that Kathleen Folbigg may have been experiencing the phenomenon known as ‘survivor guilt’.

The handwritten diaries and journal entries are in excess of 40,000 words and have only recently been transcribed.

References

[1] R v Folbigg [2003] NSWCCA 17.

[2] R Hill, ‘Multiple sudden infant deaths – coincidence or beyond coincidence?’, Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology (2004) 18, 320–326, 326.

[3] For example, see: Donald R Peterson, et al, ‘The sudden infant death syndrome: Repetitions in families’, (1980) 97(2) The Journal of Pediatrics 265-267; Dorothy H Kelly and Daniel C Shannon, ‘Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Near Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Review of the Literature, 1964 to 1982’, (1982) 29(5) Pediatric Clinics of North America, 1241-1261; Lorentz M Irgens, et al, ‘Prospective assessment of recurrence risk in sudden infant death syndrome siblings’, (1984) 104(3) The Journal of Pediatrics, 349-351; John L Emery, ‘Families in which two or more cot deaths have occurred’, (1986) The Lancet, 313-315; Eugene Diamond, ‘Sudden Infant Death In Five Consecutive Siblings’, 170(1) Illinios Medical Journal, 33-34; and Joseph Oren, et al, ‘Familial Occurrence of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Apnea of Infancy’, (1987) 80(3) Pediatrics 355-388.

[4] Cordner Report 52, 53.

[5] Inquiry report at page 163 at paragraph 282.

[6] Inquiry report at page 164 at paragraph 286.9.

[7] Brohus et al (2020) (n 6).

[8] Evidence from Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton. See inquiry transcript references: Professor Cordner at page 130 lines 23-35, page 132 line 5 (19.03.19), page 278 lines 12-16 (21.03.19); Professor Duflou at page 130 lines 8-14 (19.03.19), page 245 lines 25-31 (21.03.19); Professor Hilton at page 130 lines 18-20 (19.03.19), page 244 lines 7-16 (21.03.19). Available at: https://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/transcripts.aspx

Reports of Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton (n 1).

[9] Evidence from Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton. See inquiry transcript references: Professor Cordner at page 161 line 49 (20.03.19); Professor Duflou at page 162 lines 30-35 (20.03.19); Professor Hilton at page 147 lines 12-22 (20.03.19), page 164 lines 12-22 (20.03.19). Available at: https://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/transcripts.aspx

Reports of Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton (n 1).

Reports of Professor Monique Ryan dated 15 March 2019 (Exhibit AJ) and Report of Associate Professor Michael Fahey dated 30 March 2019 (Exhibit AK). Available at: https://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/exhibits.aspx

[10] Evidence from Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton. See inquiry transcript references: Professor Cordner at page 179 line 25 (20.03.19), page 280 line 15 (21.03.19); Professor Duflou at pages 179-180 (in full) (20.03.19), page 280 line 3 (21.03.19); Professor Hilton at page 280 line 7 (21.03.19). See also Dr Cala at page 280 line 11 (21.03.19). Available at: https://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/transcripts.aspx

Reports of Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton (n 1).

See also Brohus et al (2020) (n 6).

[11] Evidence from Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton. Professor Cordner at page 276 line 6 (21.03.19); Professor Duflou at page 276 line 3 and lines 30-35 (21.03.19); Professor Hilton at page 275 line 50 (21.03.19). See also Dr Cala: “I think, with Laura, there’s undoubtedly myocarditis and I’ve said I can’t exclude that as being the cause of death” see page 281 line 20 (21.03.19). Available at: https://www.folbigginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/transcripts.aspx

Reports of Professors Cordner, Duflou and Hilton (n 1).

[12] Brohus et al (2020) (n 6).

[13] Peter J. Schwartz, Michael J. Ackerman, Charles Antzelevitch, Connie R. Bezzina, Martin Borggrefe, Bettina F. Cuneo and Arthur A. M. Wilde, ‘Inherited cardiac arrhythmias’ (2020) 6(1) Nature Reviews Disease Primers 1-22.

[14] Brohus et al (2020) (n 6).

[15] Brohus et al (2020) (n 6): https://academic.oup.com/europace/advance-article/doi/10.1093/europace/euaa272/5983835#supplementary-data